1.1 什么是互联网?#

1.1 What Is the Internet?

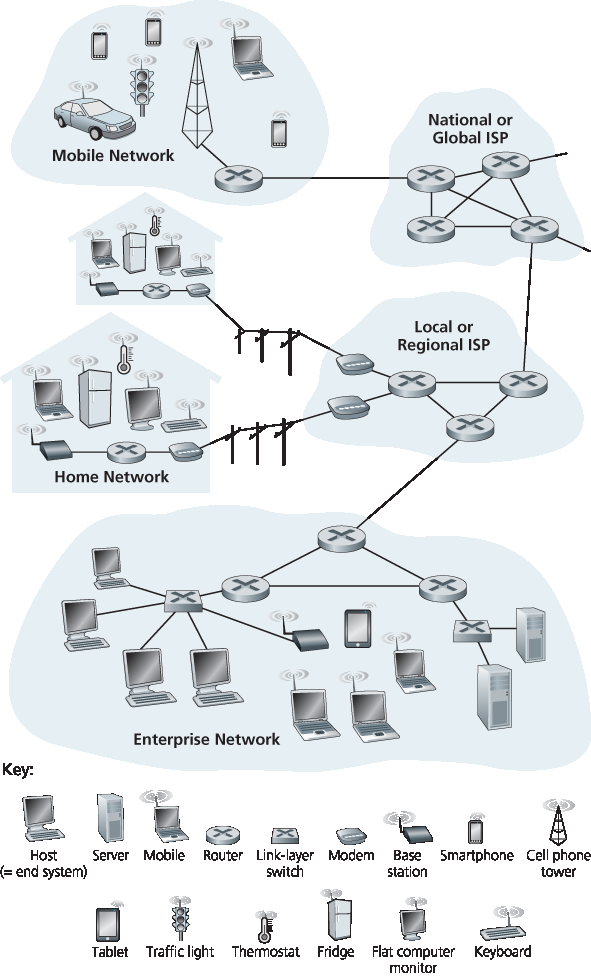

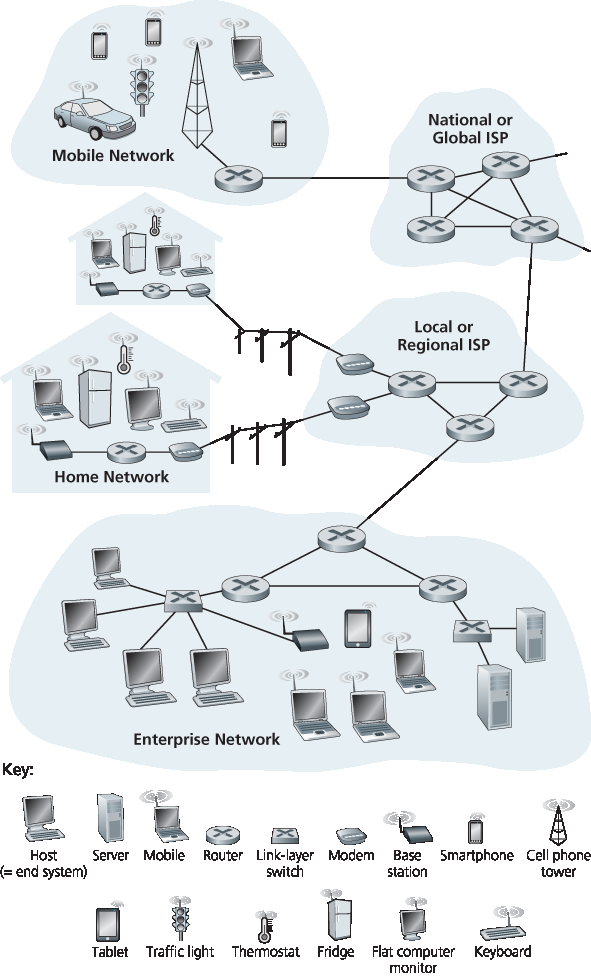

在本书中,我们将使用公共互联网这一特定的计算机网络,作为讨论计算机网络及其协议的主要载体。但什么是互联网?这个问题可以从几个角度来回答。首先,我们可以从互联网的“结构组件”角度进行描述,即构成互联网的基本硬件和软件组件。其次,我们可以将互联网描述为一个向分布式应用提供服务的网络基础设施。让我们从“结构组件”的描述开始,借助 图 1.1 展开讨论。

In this book, we’ll use the public Internet, a specific computer network, as our principal vehicle for discussing computer networks and their protocols. But what is the Internet? There are a couple of ways to answer this question. First, we can describe the nuts and bolts of the Internet, that is, the basic hardware and software components that make up the Internet. Second, we can describe the Internet in terms of a networking infrastructure that provides services to distributed applications. Let’s begin with the nuts-and-bolts description, using Figure 1.1 to illustrate our discussion.

1.1.1 结构组件描述#

1.1.1 A Nuts-and-Bolts Description

互联网是一个将全球数十亿计算设备互联的计算机网络。不久前,这些设备主要是传统的台式 PC、Linux 工作站和所谓的服务器(用于存储和传输网页和电子邮件等信息)。但现在,越来越多的“非常规”互联网“设备”接入了互联网,例如笔记本电脑、智能手机、平板电脑、电视、游戏主机、温控器、家庭安防系统、家用电器、手表、眼镜、汽车、交通控制系统等等。事实上,考虑到大量接入互联网的非传统设备,“计算机网络”这一术语已略显过时。在互联网术语中,所有这些设备被称为 主机(host) 或 端系统(end system)。据估计,2015 年大约有 50 亿设备接入互联网,到 2020 年,这一数字将达到 250 亿 [Gartner 2014]。据统计,2015 年全球互联网用户超过 32 亿人,约占全球人口的 40% [ITU 2015]。

图 1.1 互联网的组成部分

端系统通过 通信链路(communication links) 和 分组交换设备(packet switches) 连接在一起。我们将在 第 1.2 节 中看到,有多种类型的通信链路,它们由不同类型的物理介质构成,包括同轴电缆、铜线、光纤和无线电频谱。不同链路的传输速率不同,链路的 传输速率(transmission rate) 通常以 bit/s 为单位。当一个端系统有数据要发送到另一个端系统时,发送端系统会将数据分段,并为每个分段添加报头字节。这些信息包在计算机网络术语中称为 分组(packet),它们通过网络被发送到目的端系统,在那里被重新组装为原始数据。

分组交换设备接收来自某一输入通信链路的分组,并将其转发至某个输出通信链路。分组交换设备有多种形式,但当前互联网中最主要的两类是 路由器(router) 和 链路层交换机(link-layer switch)。这两类交换设备都将分组朝其最终目的地转发。链路层交换机通常用于接入网络,而路由器通常用于网络核心。从发送端系统到接收端系统,分组所经过的通信链路和分组交换设备的序列称为网络中的 路径(route 或 path)。Cisco 预测全球年 IP 流量将在 2016 年底突破 zettabyte( \(10^{21}\) 字节)门槛,并将在 2019 年达到每年 2 zettabyte [Cisco VNI 2015]。

分组交换网络(负责传输分组)在很多方面类似于运输网络(如公路、道路和交叉口,负责运送车辆)。例如,一个工厂需要将大量货物运输到数千公里外的某个仓库。工厂将货物分装到一车车卡车中,每辆卡车独立通过公路网络前往目的地仓库。在目的地,货物被卸下并重新合并。因此,分组类似于卡车,通信链路类似于公路和道路,分组交换设备类似于交叉口,端系统类似于建筑物。就像卡车会走一条运输网络的路径,分组也会走一条计算机网络的路径。

端系统通过 互联网服务提供商(Internet Service Providers,ISPs) 接入互联网,包括住宅 ISP(如本地有线或电话公司)、企业 ISP、大学 ISP、在机场、酒店和咖啡店等公共场所提供 WiFi 接入的 ISP,以及为智能手机和其他设备提供移动数据接入的蜂窝 ISP。每个 ISP 本身就是一个由分组交换设备和通信链路组成的网络。ISP 为端系统提供多种类型的网络接入方式,包括家庭宽带(如有线调制解调器或 DSL)、高速局域网接入和移动无线接入。ISP 还为内容提供商提供互联网接入,直接将网站和视频服务器连接到互联网。互联网的核心目标是实现端系统之间的互联,因此为端系统提供接入的 ISP 也必须相互连接。这些较低层的 ISP 通过全国和全球性的上层 ISP(如 Level 3 Communications、AT&T、Sprint 和 NTT)互联。一个上层 ISP 通常由高速路由器和高速光纤链路互连构成。无论是上层还是下层 ISP 网络,都独立运营,运行 IP 协议(见下文),并遵循一定的命名和地址约定。我们将在 第 1.3 节 中进一步探讨 ISP 及其互联方式。

端系统、分组交换设备以及互联网的其他组成部分都运行着 协议(protocols),这些协议控制信息在互联网中的发送和接收。其中,传输控制协议(Transmission Control Protocol, TCP) 和 互联网协议(Internet Protocol, IP) 是互联网中最重要的两个协议。IP 协议规定了路由器和端系统之间发送和接收的分组的格式。互联网的主要协议统称为 TCP/IP 协议族。我们将在本章中初步了解这些协议,但这仅是开始——本书的大部分内容都与计算机网络协议有关。

鉴于协议对互联网的重要性,确保每个协议的功能有明确的定义是至关重要的,这样人们才能创建可互操作的系统和产品。这正是标准发挥作用的地方。互联网标准(Internet standards) 由互联网工程任务组(Internet Engineering Task Force, IETF)制定 [IETF 2016]。IETF 的标准文档称为 RFC(请求评议,Requests for Comments)。RFC 最初是为了解决互联网前身所面临的网络和协议设计问题而发起的评议请求 [Allman 2011]。RFC 文档通常技术性很强,内容详尽,定义了如 TCP、IP、HTTP(Web 使用的协议)和 SMTP(电子邮件使用的协议)等协议。目前已有 7000 多份 RFC。此外,还有其他机构制定网络组件的标准,尤其是网络链路相关标准。例如 IEEE 802 LAN/MAN 标准委员会 [IEEE 802 2016] 负责指定以太网和无线 WiFi 标准。

The Internet is a computer network that interconnects billions of computing devices throughout the world. Not too long ago, these computing devices were primarily traditional desktop PCs, Linux workstations, and so-called servers that store and transmit information such as Web pages and e-mail messages. Increasingly, however, nontraditional Internet “things” such as laptops, smartphones, tablets, TVs, gaming consoles, thermostats, home security systems, home appliances, watches, eye glasses, cars, traffic control systems and more are being connected to the Internet. Indeed, the term computer network is beginning to sound a bit dated, given the many nontraditional devices that are being hooked up to the Internet. In Internet jargon, all of these devices are called hosts or end systems. By some estimates, in 2015 there were about 5 billion devices connected to the Internet, and the number will reach 25 billion by 2020 [Gartner 2014] . It is estimated that in 2015 there were over 3.2 billion Internet users worldwide, approximately 40% of the world population [ITU 2015].

Figure 1.1 Some pieces of the Internet

End systems are connected together by a network of communication links and packet switches. We’ll see in Section 1.2 that there are many types of communication links, which are made up of different types of physical media, including coaxial cable, copper wire, optical fiber, and radio spectrum. Different links can transmit data at different rates, with the transmission rate of a link measured in bits/second. When one end system has data to send to another end system, the sending end system segments the data and adds header bytes to each segment. The resulting packages of information, known as packets in the jargon of computer networks, are then sent through the network to the destination end system, where they are reassembled into the original data.

A packet switch takes a packet arriving on one of its incoming communication links and forwards that packet on one of its outgoing communication links. Packet switches come in many shapes and flavors, but the two most prominent types in today’s Internet are routers and link-layer switches. Both types of switches forward packets toward their ultimate destinations. Link-layer switches are typically used in access networks, while routers are typically used in the network core. The sequence of communication links and packet switches traversed by a packet from the sending end system to the receiving end system is known as a route or path through the network. Cisco predicts annual global IP traffic will pass the zettabyte ( \(10^{21}\) bytes) threshold by the end of 2016, and will reach 2 zettabytes per year by 2019 [Cisco VNI 2015].

Packet-switched networks (which transport packets) are in many ways similar to transportation networks of highways, roads, and intersections (which transport vehicles). Consider, for example, a factory that needs to move a large amount of cargo to some destination warehouse located thousands of kilometers away. At the factory, the cargo is segmented and loaded into a fleet of trucks. Each of the trucks then independently travels through the network of highways, roads, and intersections to the destination warehouse. At the destination warehouse, the cargo is unloaded and grouped with the rest of the cargo arriving from the same shipment. Thus, in many ways, packets are analogous to trucks, communication links are analogous to highways and roads, packet switches are analogous to intersections, and end systems are analogous to buildings. Just as a truck takes a path through the transportation network, a packet takes a path through a computer network.

End systems access the Internet through Internet Service Providers (ISPs), including residential ISPs such as local cable or telephone companies; corporate ISPs; university ISPs; ISPs that provide WiFi access in airports, hotels, coffee shops, and other public places; and cellular data ISPs, providing mobile access to our smartphones and other devices. Each ISP is in itself a network of packet switches and communication links. ISPs provide a variety of types of network access to the end systems, including residential broadband access such as cable modem or DSL, high-speed local area network access, and mobile wireless access. ISPs also provide Internet access to content providers, connecting Web sites and video servers directly to the Internet. The Internet is all about connecting end systems to each other, so the ISPs that provide access to end systems must also be interconnected. These lower-tier ISPs are interconnected through national and international upper-tier ISPs such as Level 3 Communications, AT&T, Sprint, and NTT. An upper-tier ISP consists of high-speed routers interconnected with high-speed fiber-optic links. Each ISP network, whether upper-tier or lower-tier, ismanaged independently, runs the IP protocol (see below), and conforms to certain naming and address conventions. We’ll examine ISPs and their interconnection more closely in Section 1.3.

End systems, packet switches, and other pieces of the Internet run protocols that control the sending and receiving of information within the Internet. The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the Internet Protocol (IP) are two of the most important protocols in the Internet. The IP protocol specifies the format of the packets that are sent and received among routers and end systems. The Internet’s principal protocols are collectively known as TCP/IP . We’ll begin looking into protocols in this introductory chapter. But that’s just a start—much of this book is concerned with computer network protocols!

Given the importance of protocols to the Internet, it’s important that everyone agree on what each and every protocol does, so that people can create systems and products that interoperate. This is where standards come into play. Internet standards are developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) [IETF 2016]. The IETF standards documents are called requests for comments (RFCs) . RFCs started out as general requests for comments (hence the name) to resolve network and protocol design problems that faced the precursor to the Internet [Allman 2011]. RFCs tend to be quite technical and detailed. They define protocols such as TCP, IP, HTTP (for the Web), and SMTP (for e-mail). There are currently more than 7,000 RFCs. Other bodies also specify standards for network components, most notably for network links. The IEEE 802 LAN/MAN Standards Committee [IEEE 802 2016], for example, specifies the Ethernet and wireless WiFi standards.

1.1.2 服务视角的描述#

1.1.2 A Services Description

在上面的讨论中,我们识别出了构成互联网的许多组件。但我们也可以从完全不同的角度来描述互联网 —— 即,将其视为一个为应用程序提供服务的基础设施。除了传统的应用程序,如电子邮件和网页浏览之外,互联网应用还包括移动智能手机和平板电脑应用,例如互联网消息传递、带有实时路况信息的地图、云音乐流媒体、电影和电视流媒体、在线社交网络、视频会议、多人游戏,以及基于位置的推荐系统等。这些应用被称为 分布式应用(distributed applications),因为它们涉及多个端系统之间的数据交换。需要特别指出的是,互联网应用运行在端系统上 —— 它们不会在网络核心的分组交换设备上运行。虽然分组交换设备负责端系统之间的数据传输,但它们并不关心数据所属的应用程序。

让我们进一步探讨“为应用提供服务的基础设施”这一说法。假设你有一个激动人心的分布式互联网应用创意,这个创意可能会极大地造福人类,或者(至少)让你一夜成名、赚得盆满钵满。你该如何将这个想法变成一个实际可用的互联网应用呢?由于应用程序运行在端系统上,你需要编写运行在端系统上的程序。例如,你可能会使用 Java、C 或 Python 来编写程序。由于你正在开发一个分布式互联网应用,这些运行在不同端系统上的程序需要相互发送数据。这就引出了一个关键问题 —— 这也是我们从服务平台角度描述互联网的切入点:一个运行在某个端系统上的程序,如何指示互联网将数据发送到另一个端系统上运行的程序?

接入互联网的端系统提供一个 套接字接口(socket interface),该接口规定了一个运行在端系统上的程序如何请求互联网将数据传输到另一个端系统上的特定目的程序。这个互联网套接字接口是一组规则,发送方程序必须遵循这些规则,互联网才能将数据正确地传递给目标程序。我们将在 第 2 章 中详细讨论互联网套接字接口。现在,我们先用一个简单的类比来帮助理解,这也是本书中反复使用的类比。假设 Alice 想通过邮政系统给 Bob 寄信。当然,Alice 不能只是写好信(即数据)然后直接从窗户扔出去。邮政系统要求 Alice 把信放进信封,在信封中间写上 Bob 的全名、地址和邮政编码,封好信封,在右上角贴上邮票,最后把信投进官方的邮政信箱。因此,邮政系统有一套“邮政服务接口”或规则,Alice 必须遵循这些规则,邮政系统才会为她投递信件。类似地,互联网也有一套套接字接口,发送数据的程序必须遵循这一接口,互联网才能将数据正确传递给接收数据的程序。

当然,邮政系统向客户提供的不止一种服务,它还提供特快专递、回执通知、普通投递等多种服务。互联网也类似,它为其应用程序提供了多种服务。当你开发一个互联网应用时,你也需要选择适合该应用的互联网服务类型。我们将在 第 2 章 中详细介绍互联网提供的服务。

我们刚刚从两个角度对互联网进行了描述:一个是从硬件和软件组件的角度,另一个是作为为分布式应用提供服务的平台。但你可能仍对“什么是互联网”感到困惑:什么是分组交换?什么是 TCP/IP?什么是路由器?互联网中都有哪些类型的通信链路?什么是分布式应用?一个温控器或体重秤又是如何接入互联网的?如果你现在感到有些不知所措,不必担心 —— 本书的目的正是向你介绍互联网的结构细节,以及支撑其运行机制的基本原理。我们将在接下来的各节和各章中详细解释这些关键术语与问题。

Our discussion above has identified many of the pieces that make up the Internet. But we can also describe the Internet from an entirely different angle—namely, as an infrastructure that provides services to applications. In addition to traditional applications such as e-mail and Web surfing, Internet applications include mobile smartphone and tablet applications, including Internet messaging, mapping with real-time road-traffic information, music streaming from the cloud, movie and television streaming, online social networks, video conferencing, multi-person games, and location-based recommendation systems. The applications are said to be distributed applications, since they involve multiple end systems that exchange data with each other. Importantly, Internet applications run on end systems— they do not run in the packet switches in the network core. Although packet switches facilitate the exchange of data among end systems, they are not concerned with the application that is the source or sink of data.

Let’s explore a little more what we mean by an infrastructure that provides services to applications. To this end, suppose you have an exciting new idea for a distributed Internet application, one that may greatly benefit humanity or one that may simply make you rich and famous. How might you go abouttransforming this idea into an actual Internet application? Because applications run on end systems, you are going to need to write programs that run on the end systems. You might, for example, write your programs in Java, C, or Python. Now, because you are developing a distributed Internet application, the programs running on the different end systems will need to send data to each other. And here we get to a central issue—one that leads to the alternative way of describing the Internet as a platform for applications. How does one program running on one end system instruct the Internet to deliver data to another program running on another end system?

End systems attached to the Internet provide a socket interface that specifies how a program running on one end system asks the Internet infrastructure to deliver data to a specific destination program running on another end system. This Internet socket interface is a set of rules that the sending program must follow so that the Internet can deliver the data to the destination program. We’ll discuss the Internet socket interface in detail in Chapter 2. For now, let’s draw upon a simple analogy, one that we will frequently use in this book. Suppose Alice wants to send a letter to Bob using the postal service. Alice, of course, can’t just write the letter (the data) and drop the letter out her window. Instead, the postal service requires that Alice put the letter in an envelope; write Bob’s full name, address, and zip code in the center of the envelope; seal the envelope; put a stamp in the upper-right-hand corner of the envelope; and finally, drop the envelope into an official postal service mailbox. Thus, the postal service has its own “postal service interface,” or set of rules, that Alice must follow to have the postal service deliver her letter to Bob. In a similar manner, the Internet has a socket interface that the program sending data must follow to have the Internet deliver the data to the program that will receive the data. The postal service, of course, provides more than one service to its customers. It provides express delivery, reception confirmation, ordinary use, and many more services. In a similar manner, the Internet provides multiple services to its applications. When you develop an Internet application, you too must choose one of the Internet’s services for your application. We’ll describe the Internet’s services in Chapter 2.

We have just given two descriptions of the Internet; one in terms of its hardware and software components, the other in terms of an infrastructure for providing services to distributed applications. But perhaps you are still confused as to what the Internet is. What are packet switching and TCP/IP? What are routers? What kinds of communication links are present in the Internet? What is a distributed application? How can a thermostat or body scale be attached to the Internet? If you feel a bit overwhelmed by all of this now, don’t worry—the purpose of this book is to introduce you to both the nuts and bolts of the Internet and the principles that govern how and why it works. We’ll explain these important terms and questions in the following sections and chapters.

1.1.3 什么是协议?#

1.1.3 What Is a Protocol?

在我们初步了解了什么是互联网之后,让我们来看看计算机网络中的另一个重要术语:协议(protocol)。什么是协议?协议的作用是什么?

Now that we’ve got a bit of a feel for what the Internet is, let’s consider another important buzzword in computer networking: protocol. What is a protocol? What does a protocol do?

一个类比:人类协议#

A Human Analogy

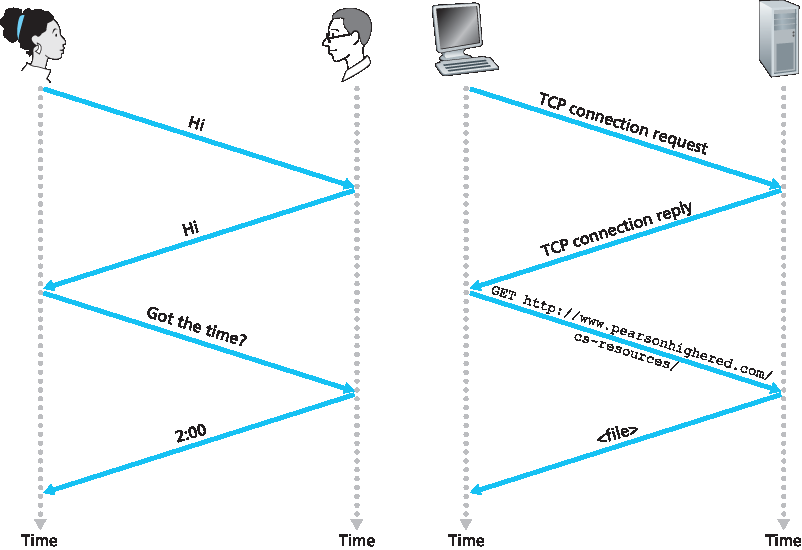

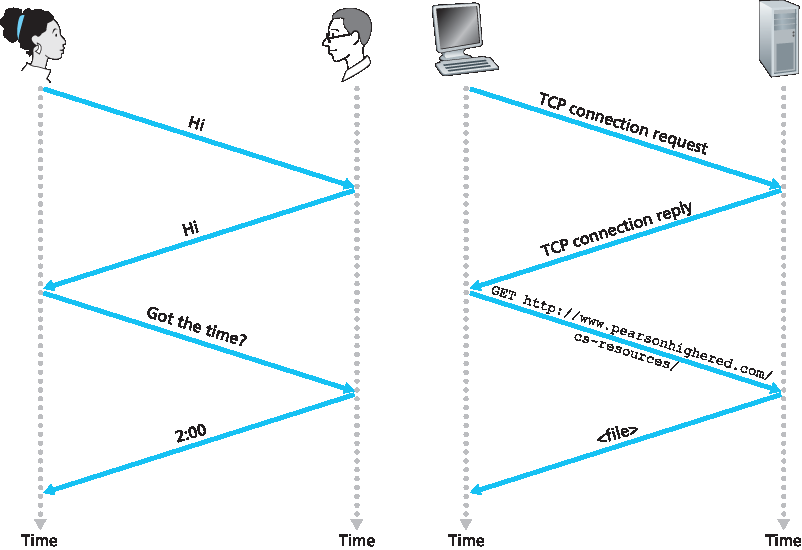

要理解计算机网络协议的概念,最容易的方式或许是先考虑一些人类行为的类比,因为我们人类在日常生活中经常执行各种协议。比如说你想问某人现在几点了,一段典型的对话可以参见 图 1.2。

人类协议(或至少是礼貌行为)规定:在和他人开始交流之前,应该先打招呼(如图中的第一个“Hi”)。通常,对方会回一个“Hi”,这表示交流可以继续。接着你就可以问“现在几点了”。如果对方的回应不是“Hi”,而是“别烦我!”、“我不会说英语”,或者是某些不可描述的话语,那么这可能表示对方不愿意或无法交流。在这种情况下,人类协议的行为是:不再继续提问。有时你甚至不会收到任何回应,这时你也会放弃继续交流。

请注意,在这个人类协议中, 我们发送特定的消息,并根据收到的回复消息或其他事件(如在设定时间内没有回复)采取特定的行动 。显然,消息的发送与接收,以及在这些消息或事件发生时所采取的行为,在人类协议中占据核心地位。如果两人遵循不同的协议(比如一人懂礼貌、另一人不懂,或者一人理解时间的概念、另一人不理解),则协议就无法互操作,最终也达不到任何有效的交流目的。网络通信中也是如此 —— 需要两个(或多个)通信实体运行相同的协议,才能完成一个任务。

图 1.2 人类协议与计算机网络协议

我们再来看一个人类协议的例子。假设你正在上一门大学课程(比如计算机网络课)。老师在讲解协议,而你感到有些困惑。这时老师停下来问:“有问题吗?”(这是一条发给所有未打瞌睡学生的广播消息)。你举手(向老师发出一个隐含的信号)。老师看到后微笑着说:“请讲……”(这是鼓励你提问的反馈消息 —— 老师都喜欢被提问),于是你提出了自己的问题(发送你的消息)。老师听到后(接收到消息)作出回应(发回一个答复)。在这个问答协议中,我们再次看到:消息的传输与接收,以及在这些消息发生时执行的一系列传统行为,构成了协议的核心内容。

It is probably easiest to understand the notion of a computer network protocol by first considering some human analogies, since we humans execute protocols all of the time. Consider what you do when you want to ask someone for the time of day. A typical exchange is shown in Figure 1.2. Human protocol (or good manners, at least) dictates that one first offer a greeting (the first “Hi” in Figure 1.2 ) to initiate communication with someone else. The typical response to a “Hi” is a returned “Hi” message. Implicitly, one then takes a cordial “Hi” response as an indication that one can proceed and ask for the time of day. A different response to the initial “Hi” (such as “Don’t bother me!” or “I don’t speak English,” or some unprintable reply) might indicate an unwillingness or inability to communicate. In this case, the human protocol would be not to ask for the time of day. Sometimes one gets no response at all to a question, in which case one typically gives up asking that person for the time. Note that in our human protocol, there are specific messageswe send, and specific actions we take in response to the received reply messages or other events (such as no reply within some given amount of time). Clearly, transmitted and received messages, and actions taken when these messages are sent or received or other events occur, play a central role in a human protocol. If people run different protocols (for example, if one person has manners but the other does not, or if one understands the concept of time and the other does not) the protocols do not interoperate and no useful work can be accomplished. The same is true in networking—it takes two (or more) communicating entities running the same protocol in order to accomplish a task.

Figure 1.2 A human protocol and a computer network protocol

Let’s consider a second human analogy. Suppose you’re in a college class (a computer networking class, for example!). The teacher is droning on about protocols and you’re confused. The teacher stops to ask, “Are there any questions?” (a message that is transmitted to, and received by, all students who are not sleeping). You raise your hand (transmitting an implicit message to the teacher). Your teacher acknowledges you with a smile, saying “Yes …” (a transmitted message encouraging you to ask your question—teachers love to be asked questions), and you then ask your question (that is, transmit your message to your teacher). Your teacher hears your question (receives your question message) and answers (transmits a reply to you). Once again, we see that the transmission and receipt of messages, and a set of conventional actions taken when these messages are sent and received, are at the heart of this question-and-answer protocol.

网络协议#

Network Protocols

网络协议类似于人类协议,但消息交换和动作执行的实体是设备中的硬件或软件组件(例如计算机、智能手机、平板、路由器或其他具备网络功能的设备)。互联网上涉及两个或多个远程通信实体的所有活动都由协议控制。例如,在两台物理连接的计算机中,硬件实现的协议控制着两块网卡之间的比特流;在端系统中,拥塞控制协议控制着发送方和接收方之间分组的发送速率;在路由器中,协议决定了分组从源头到目的地的路径。协议无处不在,因此本书的大部分内容都是在讲计算机网络协议。

举一个你可能熟悉的例子:当你在浏览器中输入一个网页 URL 请求某个 Web 服务器时,会发生什么?这个场景如图 1.2 的右半部分所示。首先,你的计算机会向 Web 服务器发送一个连接请求消息,并等待回复。Web 服务器收到连接请求后,会返回一个连接确认消息。得知可以请求 Web 文档后,你的计算机发送一个 GET 消息,告诉服务器你希望获取哪个网页。最后,Web 服务器将该网页文件发送回你的计算机。

从上述人类和网络的例子中可以看到,协议的定义核心在于消息的交换以及在这些消息被发送和接收时所采取的行为:

一个 协议(protocol) 定义了两个或多个通信实体之间所交换消息的格式与顺序,以及在发送或接收消息或发生其他事件时采取的动作。

互联网(以及更广泛的计算机网络)大量使用协议。不同的通信任务使用不同的协议。你在阅读本书的过程中将会发现,有些协议简单直接,而有些则复杂深奥。掌握计算机网络这一领域,实际上就是理解网络协议的“是什么”、“为什么”与“如何实现”。

A network protocol is similar to a human protocol, except that the entities exchanging messages and taking actions are hardware or software components of some device (for example, computer, smartphone, tablet, router, or other network-capable device). All activity in the Internet that involves two or more communicating remote entities is governed by a protocol. For example, hardware-implemented protocols in two physically connected computers control the flow of bits on the “wire” between the two network interface cards; congestion-control protocols in end systems control the rate at which packets are transmitted between sender and receiver; protocols in routers determine a packet’s path from source to destination. Protocols are running everywhere in the Internet, and consequently much of this book is about computer network protocols.

As an example of a computer network protocol with which you are probably familiar, consider what happens when you make a request to a Web server, that is, when you type the URL of a Web page into your Web browser. The scenario is illustrated in the right half of Figure 1.2 . First, your computer will send a connection request message to the Web server and wait for a reply. The Web server will eventually receive your connection request message and return a connection reply message. Knowing that it is now OK to request the Web document, your computer then sends the name of the Web page it wants to fetch from that Web server in a GET message. Finally, the Web server returns the Web page (file) to your computer.

Given the human and networking examples above, the exchange of messages and the actions taken when these messages are sent and received are the key defining elements of a protocol:

A protocol defines the format and the order of messages exchanged between two or more communicating entities, as well as the actions taken on the transmission and/or receipt of a message or other event.

The Internet, and computer networks in general, make extensive use of protocols. Different protocols are used to accomplish different communication tasks. As you read through this book, you will learn that some protocols are simple and straightforward, while others are complex and intellectually deep. Mastering the field of computer networking is equivalent to understanding the what, why, and how of networking protocols.