9.2 流媒体存储视频#

9.2 Streaming Stored Video

对于流媒体视频应用,预录制的视频被放置在服务器上,用户向这些服务器发送请求以按需观看视频。用户可以从头到尾 uninterrupted 地观看视频,可以在视频结束前停止观看,或通过暂停、前进或后退等方式与视频进行交互。流媒体视频系统可分为三类: UDP 流媒体、 HTTP 流媒体 和 自适应 HTTP 流媒体 (见 Section 2.6)。尽管这三种系统在实际中都被使用,但如今大多数系统采用 HTTP 流媒体和自适应 HTTP 流媒体。

所有三种视频流媒体形式的一个共同特点是广泛使用客户端应用程序缓冲区,以减轻服务器到客户端之间端到端延迟的变化和可用带宽变化的影响。对于流媒体视频(无论是存储的还是直播的),用户通常可以容忍在客户端请求视频和视频开始播放之间几秒钟的小延迟。因此,当视频开始到达客户端时,客户端不需要立即开始播放,而是可以先在应用程序缓冲区中积累一定的视频储备。一旦客户端积累了几秒钟尚未播放的视频储备,便可以开始播放视频。这种 客户端缓冲 提供了两个重要优势。首先,客户端缓冲可以吸收服务器到客户端延迟的变化。如果某一段视频数据延迟,只要它在已接收但尚未播放的视频储备耗尽前到达,用户就不会注意到这个长延迟。其次,如果服务器到客户端的带宽短暂下降到低于视频消费速率的水平,只要客户端应用程序缓冲区未完全耗尽,用户仍可持续播放不中断。

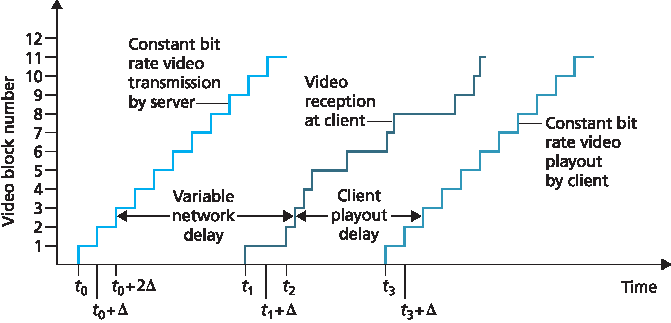

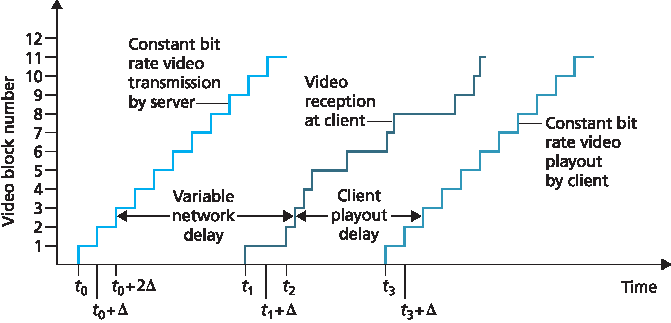

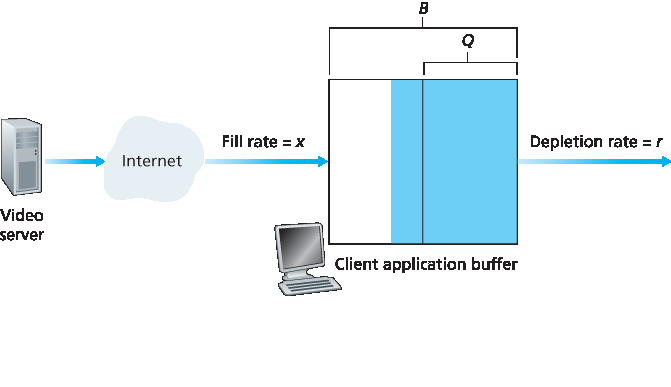

Figure 9.1 展示了客户端缓冲。假设视频以固定比特率编码,因此每个视频块包含在固定时间 Δ 内播放的帧。服务器在 t0 发送第一个视频块,在 t0+Δ 发送第二个,在 t0+2Δ 发送第三个,以此类推。一旦客户端开始播放,每个块应在前一个块播放 Δ 时间单位后播放,以重现原始录制视频的时间序列。由于网络端到端延迟的可变性,不同视频块经历的延迟不同。第一个视频块在 t1 到达客户端,第二个在 t2 到达。第 i 个块的网络延迟是服务器发送该块的时间与客户端接收时间之间的水平距离;注意,不同视频块的网络延迟是不同的。在此示例中,如果客户端在 t1 即第一个块到达时就开始播放,则第二个块无法及时在 t1+Δ 时播放。此时,要么播放中断等待第 2 块到达,要么跳过第 2 块播放——这两种情况都会带来不良的播放体验。相反,如果客户端延迟播放到 t3,此时块 1 到 6 都已到达,则可以按照固定节奏开始播放,且每个块都能在其播放时间前到达。

Figure 9.1 视频流媒体中的客户端播放延迟

For streaming video applications, prerecorded videos are placed on servers, and users send requests to these servers to view the videos on demand. The user may watch the video from beginning to end without interruption, may stop watching the video well before it ends, or interact with the video by pausing or repositioning to a future or past scene. Streaming video systems can be classified into three categories: UDP streaming, HTTP streaming, and adaptive HTTP streaming (see Section 2.6). Although all three types of systems are used in practice, the majority of today’s systems employ HTTP streaming and adaptive HTTP streaming.

A common characteristic of all three forms of video streaming is the extensive use of client-side application buffering to mitigate the effects of varying end-to-end delays and varying amounts of available bandwidth between server and client. For streaming video (both stored and live), users generally can tolerate a small several-second initial delay between when the client requests a video and when video playout begins at the client. Consequently, when the video starts to arrive at the client, the client need not immediately begin playout, but can instead build up a reserve of video in an application buffer. Once the client has built up a reserve of several seconds of buffered-but-not-yet-played video, the client can then begin video playout. There are two important advantages provided by such client buffering. First, client-side buffering can absorb variations in server-to-client delay. If a particular piece of video data is delayed, as long as it arrives before the reserve of received-but-not-yet-played video is exhausted, this long delay will not be noticed. Second, if the server-to-client bandwidth briefly drops below the video consumption rate, a user can continue to enjoy continuous playback, again as long as the client application buffer does not become completely drained.

Figure 9.1 illustrates client-side buffering. In this simple example, suppose that video is encoded at a fixed bit rate, and thus each video block contains video frames that are to be played out over the same fixed amount of time, Δ. The server transmits the first video block at t0, the second block at t0+Δ, the third block at t0+2Δ, and so on. Once the client begins playout, each block should be played out Δ time units after the previous block in order to reproduce the timing of the original recorded video. Because of the variable end-to-end network delays, different video blocks experience different delays. The first video block arrives at the client at t1 and the second block arrives at t2. The network delay for the ith block is the horizontal distance between the time the block was transmitted by the server and the time it is received at the client; note that the network delay varies from one video block to another. In this example, if the client were to begin playout as soon as the first block arrived at t1, then the second block would not have arrived in time to be played out at out at t1+Δ. In this case, video playout would either have to stall (waiting for block 2 to arrive) or block 2 could be skipped—both resulting in undesirable playout impairments. Instead, if the client were to delay the start of playout until t3, when blocks 1 through 6 have all arrived, periodic playout can proceed with all blocks having been received before their playout time.

Figure 9.1 Client playout delay in video streaming

9.2.1 UDP 流媒体#

9.2.1 UDP Streaming

我们这里只简要讨论 UDP 流媒体,更深入的协议内容可参考其他章节。在 UDP 流媒体中,服务器以与客户端视频消费速率匹配的速率,通过 UDP 稳定地发送视频块。例如,如果视频消费速率为 2 Mbps,每个 UDP 包携带 8,000 位视频数据,则服务器每 (8000 位)/(2 Mbps)=4 毫秒 向其套接字发送一个 UDP 包。正如我们在 Chapter 3 中所学,UDP 不使用拥塞控制机制,因此服务器可以按视频消费速率向网络推送数据包,不受 TCP 速率控制限制。UDP 流媒体通常使用一个很小的客户端缓冲区,仅能容纳不到一秒的视频。

在传递给 UDP 之前,服务器会将视频块封装在专门为传输音视频设计的传输包中,使用实时传输协议(RTP)[RFC 3550] 或类似(可能是专有)的协议。我们将延迟到 Section 9.3 讨论 RTP,在那里我们将其与实时语音视频系统一起讨论。

UDP 流媒体的另一个特点是,除了服务器到客户端的视频流之外,客户端和服务器还维护一个并行的控制连接,客户端通过该连接发送有关会话状态变化的命令(如暂停、继续、跳转等)。实时流媒体协议(RTSP)[RFC 2326] 是一种常用的开放控制协议,详细说明见本教材网站。

尽管 UDP 流媒体被许多开源系统和专有产品采用,但它存在三个主要缺点。首先,由于服务器与客户端之间的可用带宽不可预测且不断变化,固定速率的 UDP 流媒体难以实现连续播放。例如,考虑视频消费速率为 1 Mbps,而服务器到客户端的可用带宽通常大于 1 Mbps,但每隔几分钟就会下降至低于 1 Mbps 几秒钟的情况。在这种情况下,以 1 Mbps 恒定速率通过 RTP/UDP 发送视频的系统可能会在带宽下降后很快出现卡顿或跳帧,导致用户体验不佳。第二个缺点是,UDP 流媒体需要一个媒体控制服务器,如 RTSP 服务器,来处理客户端发来的交互请求,并为每个客户端会话追踪状态(如播放点、播放/暂停状态等)。这会增加大规模视频点播系统部署的整体成本和复杂度。第三个缺点是,许多防火墙配置为阻止 UDP 流量,阻碍了这些防火墙后方的用户接收 UDP 视频。

We only briefly discuss UDP streaming here, referring the reader to more in-depth discussions of the protocols behind these systems where appropriate. With UDP streaming, the server transmits video at a rate that matches the client’s video consumption rate by clocking out the video chunks over UDP at a steady rate. For example, if the video consumption rate is 2 Mbps and each UDP packet carries 8,000 bits of video, then the server would transmit one UDP packet into its socket every (8000 bits)/(2 Mbps)=4 msec. As we learned in Chapter 3, because UDP does not employ a congestion-control mechanism, the server can push packets into the network at the consumption rate of the video without the rate-control restrictions of TCP. UDP streaming typically uses a small client-side buffer, big enough to hold less than a second of video.

Before passing the video chunks to UDP, the server will encapsulate the video chunks within transport packets specially designed for transporting audio and video, using the Real-Time Transport Protocol (RTP) [RFC 3550] or a similar (possibly proprietary) scheme. We delay our coverage of RTP until Section 9.3, where we discuss RTP in the context of conversational voice and video systems.

Another distinguishing property of UDP streaming is that in addition to the server-to-client video stream, the client and server also maintain, in parallel, a separate control connection over which the client sends commands regarding session state changes (such as pause, resume, reposition, and so on). The Real-Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP) [RFC 2326], explained in some detail in the Web site for this textbook, is a popular open protocol for such a control connection.

Although UDP streaming has been employed in many open-source systems and proprietary products, it suffers from three significant drawbacks. First, due to the unpredictable and varying amount of available bandwidth between server and client, constant-rate UDP streaming can fail to provide continuous playout. For example, consider the scenario where the video consumption rate is 1 Mbps and the server-to-client available bandwidth is usually more than 1 Mbps, but every few minutes the available bandwidth drops below 1 Mbps for several seconds. In such a scenario, a UDP streaming system that transmits video at a constant rate of 1 Mbps over RTP/UDP would likely provide a poor user experience, with freezing or skipped frames soon after the available bandwidth falls below 1 Mbps. The second drawback of UDP streaming is that it requires a media control server, such as an RTSP server, to process client-to-server interactivity requests and to track client state (e.g., the client’s playout point in the video, whether the video is being paused or played, and so on) for each ongoing client session. This increases the overall cost and complexity of deploying a large-scale video-on-demand system. The third drawback is that many firewalls are configured to block UDP traffic, preventing the users behind these firewalls from receiving UDP video.

9.2.2 HTTP 流媒体#

9.2.2 HTTP Streaming

在 HTTP 流媒体中,视频作为一个普通文件被存储在 HTTP 服务器上,并具有一个特定的 URL。当用户想观看该视频时,客户端通过 TCP 与服务器建立连接,并发出一个针对该 URL 的 HTTP GET 请求。随后,服务器通过 HTTP 响应消息尽可能快地发送该视频文件,即在 TCP 拥塞控制和流量控制允许的范围内尽快发送。在客户端,字节被收集到客户端应用程序缓冲区中。一旦缓冲区中的字节数超过预定阈值,客户端应用程序开始播放——具体而言,它定期从应用程序缓冲区中提取视频帧,对帧进行解压缩,并在用户屏幕上显示。

我们在 Chapter 3 中了解到,通过 TCP 传输文件时,由于 TCP 拥塞控制机制,服务器到客户端的传输速率可能会显著波动。尤其常见的是传输速率以与 TCP 拥塞控制相关的“锯齿状”方式变化。此外,由于 TCP 的重传机制,数据包也可能会显著延迟。由于 TCP 具有这些特性,1990 年代的普遍看法是视频流媒体在 TCP 上无法良好运行。然而,随着时间的推移,流媒体系统的设计者认识到,若结合客户端缓冲和预取(将在下一节中讨论),TCP 的拥塞控制和可靠数据传输机制并不会妨碍连续播放。

在 TCP 上使用 HTTP 还可以更容易地穿越防火墙和 NAT(这些通常配置为阻止大多数 UDP 流量但允许大多数 HTTP 流量)。通过 HTTP 进行流媒体传输也消除了对媒体控制服务器(如 RTSP 服务器)的需求,从而降低了在互联网上大规模部署的成本。由于上述种种优点,如今大多数视频流媒体应用(包括 YouTube 和 Netflix)都采用基于 TCP 的 HTTP 流媒体作为其底层传输协议。

In HTTP streaming, the video is simply stored in an HTTP server as an ordinary file with a specific URL. When a user wants to see the video, the client establishes a TCP connection with the server and issues an HTTP GET request for that URL. The server then sends the video file, within an HTTP response message, as quickly as possible, that is, as quickly as TCP congestion control and flow control will allow. On the client side, the bytes are collected in a client application buffer. Once the number of bytes in this buffer exceeds a predetermined threshold, the client application begins playback—specifically, it periodically grabs video frames from the client application buffer, decompresses the frames, and displays them on the user’s screen.

We learned in Chapter 3 that when transferring a file over TCP, the server-to-client transmission rate can vary significantly due to TCP’s congestion control mechanism. In particular, it is not uncommon for the transmission rate to vary in a “saw-tooth” manner associated with TCP congestion control. Furthermore, packets can also be significantly delayed due to TCP’s retransmission mechanism. Because of these characteristics of TCP, the conventional wisdom in the 1990s was that video streaming would never work well over TCP. Over time, however, designers of streaming video systems learned that TCP’s congestion control and reliable-data transfer mechanisms do not necessarily preclude continuous playout when client buffering and prefetching (discussed in the next section) are used.

The use of HTTP over TCP also allows the video to traverse firewalls and NATs more easily (which are often configured to block most UDP traffic but to allow most HTTP traffic). Streaming over HTTP also obviates the need for a media control server, such as an RTSP server, reducing the cost of a large- scale deployment over the Internet. Due to all of these advantages, most video streaming applications today—including YouTube and Netflix—use HTTP streaming (over TCP) as its underlying streaming protocol.

预取视频#

Prefetching Video

正如我们刚刚了解的,客户端缓冲可用于缓解端到端延迟和可用带宽变化的影响。在 Figure 9.1 的示例中,服务器以与视频播放速率相同的速率传输视频。然而,对于存储视频流媒体,客户端可以尝试以高于消费速率的速率下载视频,从而 预取 未来将被消费的视频帧。预取的视频自然会存储在客户端应用程序缓冲区中。

在 TCP 流媒体中,预取行为会自然发生,因为 TCP 的拥塞避免机制会尝试使用服务器与客户端之间的全部可用带宽。为了更直观地理解预取,让我们来看一个简单的例子。假设视频消费速率为 1 Mbps,而网络能以恒定速率 1.5 Mbps 从服务器传送数据给客户端。那么客户端不仅可以在极小的播放延迟下播放视频,还可以每秒增加 500 Kbit 的缓冲数据。通过这种方式,如果将来客户端在某一段时间内接收速率降至低于 1 Mbps,它仍能因缓冲储备而实现连续播放。[Wang 2008] 研究表明,当平均 TCP 吞吐量约为媒体比特率的两倍时,通过 TCP 进行流媒体传输可实现最小的播放中断和极低的缓冲延迟。

As we just learned, client-side buffering can be used to mitigate the effects of varying end-to-end delays and varying available bandwidth. In our earlier example in Figure 9.1, the server transmits video at the rate at which the video is to be played out. However, for streaming stored video, the client can attempt to download the video at a rate higher than the consumption rate, thereby prefetching video frames that are to be consumed in the future. This prefetched video is naturally stored in the client application buffer.

Such prefetching occurs naturally with TCP streaming, since TCP’s congestion avoidance mechanism will attempt to use all of the available bandwidth between server and client. To gain some insight into prefetching, let’s take a look at a simple example. Suppose the video consumption rate is 1 Mbps but the network is capable of delivering the video from server to client at a constant rate of 1.5 Mbps. Then the client will not only be able to play out the video with a very small playout delay, but will also be able to increase the amount of buffered video data by 500 Kbits every second. In this manner, if in the future the client receives data at a rate of less than 1 Mbps for a brief period of time, the client will be able to continue to provide continuous playback due to the reserve in its buffer. [Wang 2008] shows that when the average TCP throughput is roughly twice the media bit rate, streaming over TCP results in minimal starvation and low buffering delays.

客户端应用程序缓冲与 TCP 缓冲#

Client Application Buffer and TCP Buffers

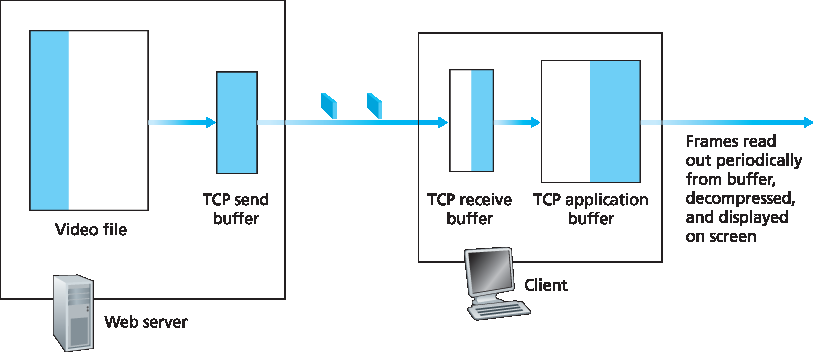

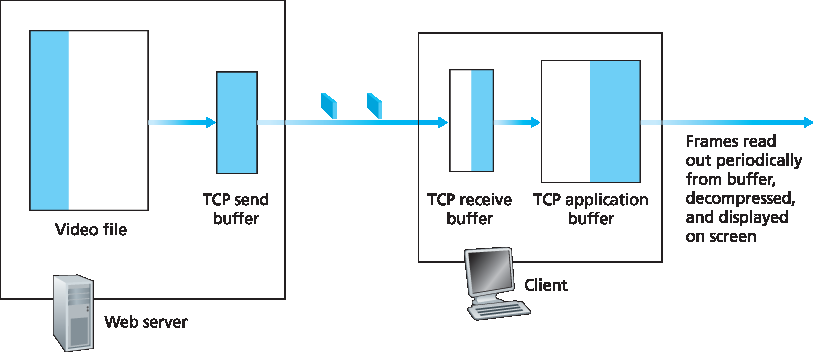

Figure 9.2 展示了 HTTP 流媒体中客户端与服务器的交互。在服务器端,图中白色部分代表已经发送到服务器套接字中的视频文件内容,深色部分代表尚未发送的部分。通过“套接字门”后,字节将被放入 TCP 发送缓冲区,然后传输至互联网,如 Chapter 3 中所述。在 Figure 9.2 中,由于服务器端 TCP 发送缓冲区已满,服务器暂时无法将更多视频字节写入套接字。在客户端,客户端应用程序(媒体播放器)从 TCP 接收缓冲区中读取字节(通过其客户端套接字)并放入客户端应用程序缓冲区。同时,客户端应用程序定期从应用程序缓冲区中提取视频帧、解压并在用户屏幕上显示。请注意,如果客户端应用程序缓冲区大于视频文件,则整个从服务器存储传输到客户端应用程序缓冲区的过程就等同于一个普通的 HTTP 文件下载——客户端只需以 TCP 所允许的最大速率从服务器拉取视频!

Figure 9.2 通过 HTTP/TCP 传输的存储视频流

接下来考虑用户在流媒体播放过程中暂停视频时会发生什么。在暂停期间,客户端应用程序缓冲区中的位不会被消耗,即使服务器仍在继续传输数据。如果客户端应用程序缓冲区是有限的,它最终可能会被填满,这将导致“反向压力”一直传递回服务器。具体来说,一旦客户端应用程序缓冲区填满,TCP 接收缓冲区中的字节将无法被移除,也就会被填满。此后,服务器端的 TCP 发送缓冲区也将无法移除字节,因此也会填满。一旦 TCP 填满,服务器就无法再向套接字发送任何字节。因此,当用户暂停视频时,服务器可能被迫停止传输,直到用户恢复播放。

事实上,即使在正常播放过程中(即未暂停时),如果客户端应用程序缓冲区已满,反向压力也会导致 TCP 缓冲区填满,从而迫使服务器降低其发送速率。要确定其结果速率,请注意,当客户端应用程序移除 f 位时,会为 f 位腾出空间,从而允许服务器发送 f 位。因此,当通过 HTTP 进行流媒体传输时,服务器发送速率不能高于客户端的视频消费速率。由此可见,客户端应用程序缓冲区已满间接限制了从服务器到客户端的视频传输速率。

Figure 9.2 illustrates the interaction between client and server for HTTP streaming. At the server side, the portion of the video file in white has already been sent into the server’s socket, while the darkened portion is what remains to be sent. After “passing through the socket door,” the bytes are placed in the TCP send buffer before being transmitted into the Internet, as described in Chapter 3. In Figure 9.2, because the TCP send buffer at the server side is shown to be full, the server is momentarily prevented from sending more bytes from the video file into the socket. On the client side, the client application (media player) reads bytes from the TCP receive buffer (through its client socket) and places the bytes into the client application buffer. At the same time, the client application periodically grabs video frames from the client application buffer, decompresses the frames, and displays them on the user’s screen. Note that if the client application buffer is larger than the video file, then the whole process of moving bytes from the server’s storage to the client’s application buffer is equivalent to an ordinary file download over HTTP—the client simply pulls the video off the server as fast as TCP will allow!

Figure 9.2 Streaming stored video over HTTP/TCP

Consider now what happens when the user pauses the video during the streaming process. During the pause period, bits are not removed from the client application buffer, even though bits continue to enter the buffer from the server. If the client application buffer is finite, it may eventually become full, which will cause “back pressure” all the way back to the server. Specifically, once the client application buffer becomes full, bytes can no longer be removed from the client TCP receive buffer, so it too becomes full. Once the client receive TCP buffer becomes full, bytes can no longer be removed from the server TCP send buffer, so it also becomes full. Once the TCP becomes full, the server cannot send any more bytes into the socket. Thus, if the user pauses the video, the server may be forced to stop transmitting, in which case the server will be blocked until the user resumes the video.

In fact, even during regular playback (that is, without pausing), if the client application buffer becomes full, back pressure will cause the TCP buffers to become full, which will force the server to reduce its rate. To determine the resulting rate, note that when the client application removes f bits, it creates room for f bits in the client application buffer, which in turn allows the server to send f additional bits. Thus, the server send rate can be no higher than the video consumption rate at the client. Therefore, a full client application buffer indirectly imposes a limit on the rate that video can be sent from server to client when streaming over HTTP.

视频流分析#

Analysis of Video Streaming

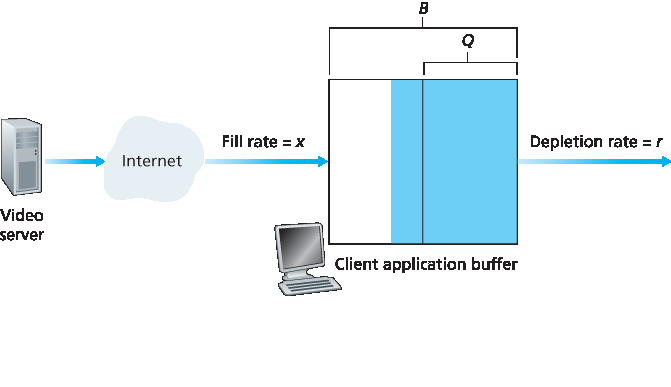

一些简单的建模可以帮助我们更深入理解初始播放延迟和因应用程序缓冲区耗尽而导致的播放冻结。如 Figure 9.3 所示,令 B 表示客户端应用程序缓冲区的大小(以比特为单位),Q 表示在客户端应用程序开始播放前需要缓冲的比特数(显然,Q<B)。令 r 表示视频消费速率——即客户端在播放过程中从缓冲区中提取比特的速率。例如,如果视频帧率为 30 帧/秒,每帧(压缩后)为 100,000 比特,则 r=3 Mbps。为了简化分析,我们暂不考虑 TCP 的发送和接收缓冲区。

Figure 9.3 通过 HTTP/TCP 传输的存储视频流

假设只要客户端缓冲区未满,服务器就以恒定速率 x 发送比特。(这显然是简化处理,因为 TCP 发送速率会随拥塞控制变化;我们将在本章末的习题中研究时间相关的速率 x(t)。)假设在 t=0 时应用程序缓冲区为空,视频开始向客户端缓冲区到达。我们现在要问的是播放将在什么时间 t=tp 开始?客户端缓冲区在什么时候 t=tf 被填满?

首先确定 tp,即 Q 比特进入缓冲区、播放开始的时间。由于在播放开始前比特是以速率 x 进入客户端缓冲区,且未被移除,因此积累 Q 比特所需时间为 tp=Q/x。

现在确定 tf,即客户端缓冲区填满的时间。如果 x<r(即服务器发送速率小于消费速率),则客户端缓冲区永远不会被填满!确实,从时间 tp 起,缓冲区以速率 r 被耗尽,但仅以 x<r 的速率补充。最终,客户端缓冲区将完全清空,视频将在屏幕上冻结,客户端缓冲区又需等待 tp 秒才能重新积累 Q 比特视频。也就是说,当网络可用速率低于视频速率时,播放将在连续播放与冻结之间交替。在作业中,你将被要求根据 Q、r 和 x 求出每段连续播放和冻结期的长度。现在我们来求当 x>r 时的 tf。在这种情况下,从时间 tp 起,缓冲区将以 x−r 的速率从 Q 增加至 B,因为比特以 x 的速率到达,以 r 的速率被消耗,如 Figure 9.3 所示。根据这些提示,你将在作业中被要求求出 tf,即客户端缓冲区填满的时间。注意,在网络可用速率高于视频速率的情况下,经过初始缓冲延迟后,用户将享受持续的播放直到视频结束。

Some simple modeling will provide more insight into initial playout delay and freezing due to application buffer depletion. As shown in Figure 9.3, let B denote the size (in bits) of the client’s application buffer, and let Q denote the number of bits that must be buffered before the client application begins playout. (Of course, Q<B.) Let r denote the video consumption rate—the rate at which the client draws bits out of the client application buffer during playback. So, for example, if the video’s frame rate is 30 frames/sec, and each (compressed) frame is 100,000 bits, then r=3 Mbps. To see the forest through the trees, we’ll ignore TCP’s send and receive buffers.

Figure 9.3 Streaming stored video over HTTP/TCP

Let’s assume that the server sends bits at a constant rate x whenever the client buffer is not full. (This is a gross simplification, since TCP’s send rate varies due to congestion control; we’ll examine more realistic time-dependent rates x(t) in the problems at the end of this chapter.) Suppose at time t=0, the application buffer is empty and video begins arriving to the client application buffer. We now ask at what time t=tp does playout begin? And while we are at it, at what time t=tf does the client application buffer become full?

First, let’s determine tp, the time when Q bits have entered the application buffer and playout begins. Recall that bits arrive to the client application buffer at rate x and no bits are removed from this buffer before playout begins. Thus, the amount of time required to build up Q bits (the initial buffering delay) is tp=Q/x.

Now let’s determine tf, the point in time when the client application buffer becomes full. We first observe that if x<r (that is, if the server send rate is less than the video consumption rate), then the client buffer will never become full! Indeed, starting at time tp, the buffer will be depleted at rate r and will only be filled at rate x<r. Eventually the client buffer will empty out entirely, at which time the video will freeze on the screen while the client buffer waits another tp seconds to build up Q bits of video. Thus, when the available rate in the network is less than the video rate, playout will alternate between periods of continuous playout and periods of freezing. In a homework problem, you will be asked to determine the length of each continuous playout and freezing period as a function of Q, r, and x. Now let’s determine tf for when x>r. In this case, starting at time tp, the buffer increases from Q to B at rate x−r since bits are being depleted at rate r but are arriving at rate x, as shown in Figure 9.3. Given these hints, you will be asked in a homework problem to determine tf, the time the client buffer becomes full. Note that when the available rate in the network is more than the video rate, after the initial buffering delay, the user will enjoy continuous playout until the video ends.

提前终止与视频重定位#

Early Termination and Repositioning the Video

HTTP 流媒体系统通常在 HTTP GET 请求消息中使用 **HTTP 字节范围头部**(HTTP byte-range header),该头部指定客户端当前希望从所请求视频中获取的字节范围。当用户想跳转到视频中某一未来时刻时,这项功能尤为重要。当用户跳转至新位置时,客户端会发送一个新的 HTTP 请求,并通过字节范围头部指明服务器应从文件中的哪个字节开始发送数据。当服务器收到这个新的 HTTP 请求时,可以忽略之前的请求,改为从该字节位置开始发送数据。

在讨论重定位时,我们还顺便提到,当用户跳转至视频中某个未来位置或提早结束观看时,服务器发送的某些已预取但尚未观看的数据将被浪费掉,这就造成了网络带宽和服务器资源的浪费。例如,假设在某个时间点 t₀,客户端缓冲区中已满(即包含 B 比特的数据),而此时用户跳转至视频中的某个时间点 t>t₀+B/r,并从该点开始观看直至结束。在这种情况下,缓冲区中的全部 B 比特数据将不被观看,而这些数据所占用的带宽和服务器资源也就完全被浪费了。由于提前终止而造成的网络带宽浪费在互联网中非常普遍,尤其在无线链路中代价尤为高昂 [Ihm 2011]。因此,许多流媒体系统仅使用中等大小的客户端应用程序缓冲区,或通过在 HTTP 请求中使用字节范围头部限制预取视频的量 [Rao 2011]。

视频重定位和提前终止就像是做了一顿大餐,却只吃了一部分,其余的都倒掉了,因而造成食物浪费。因此,下次当你的父母批评你没有吃完晚饭浪费食物时,你可以迅速反驳说他们在上网看电影时跳转画面也在浪费带宽和服务器资源!不过当然了,两件错事并不能相互抵消——无论是食物还是带宽,都不应被浪费!

在 Sections 9.2.1 和 9.2.2 中,我们分别介绍了 UDP 流媒体和 HTTP 流媒体。第三种流媒体类型是基于 HTTP 的动态自适应流媒体(Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP,DASH),它使用多个不同压缩率的视频版本。DASH 的详细内容在 Section 2.6.2 中介绍。CDN(内容分发网络)常用于分发存储视频和实时视频,相关内容将在 Section 2.6.3 中详细介绍。

HTTP streaming systems often make use of the HTTP byte-range header in the HTTP GET request message, which specifies the specific range of bytes the client currently wants to retrieve from the desired video. This is particularly useful when the user wants to reposition (that is, jump) to a future point in time in the video. When the user repositions to a new position, the client sends a new HTTP request, indicating with the byte-range header from which byte in the file should the server send data. When the server receives the new HTTP request, it can forget about any earlier request and instead send bytes beginning with the byte indicated in the byte-range request.

While we are on the subject of repositioning, we briefly mention that when a user repositions to a future point in the video or terminates the video early, some prefetched-but-not-yet-viewed data transmitted by the server will go unwatched—a waste of network bandwidth and server resources. For example, suppose that the client buffer is full with B bits at some time t0 into the video, and at this time the user repositions to some instant t>t0+B/r into the video, and then watches the video to completion from that point on. In this case, all B bits in the buffer will be unwatched and the bandwidth and server resources that were used to transmit those B bits have been completely wasted. There is significant wasted bandwidth in the Internet due to early termination, which can be quite costly, particularly for wireless links [Ihm 2011]. For this reason, many streaming systems use only a moderate-size client application buffer, or will limit the amount of prefetched video using the byte-range header in HTTP requests [Rao 2011].

Repositioning and early termination are analogous to cooking a large meal, eating only a portion of it, and throwing the rest away, thereby wasting food. So the next time your parents criticize you for wasting food by not eating all your dinner, you can quickly retort by saying they are wasting bandwidth and server resources when they reposition while watching movies over the Internet! But, of course, two wrongs do not make a right—both food and bandwidth are not to be wasted!

In Sections 9.2.1 and 9.2.2, we covered UDP streaming and HTTP streaming, respectively. A third type of streaming is Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP (DASH), which uses multiple versions of the video, each compressed at a different rate. DASH is discussed in detail in Section 2.6.2. CDNs are often used to distribute stored and live video. CDNs are discussed in detail in Section 2.6.3.