8.1 什么是网络安全?#

8.1 What Is Network Security?

让我们通过回到我们的恋人 Alice 和 Bob 的故事开始对网络安全的学习,他们想要“安全地”通信。这究竟意味着什么?当然,Alice 只希望 Bob 能理解她发送的消息,尽管他们是在一个不安全的媒介上通信,可能会被入侵者(Trudy,入侵者)拦截从 Alice 到 Bob 传输的内容。Bob 也想确认他收到的消息确实是 Alice 发送的,Alice 也想确认她通信的对象确实是 Bob。Alice 和 Bob 还希望确保消息内容在传输过程中未被篡改。他们还希望能够确认自己能够进行通信(即没有人拒绝他们访问通信所需资源)。基于这些考虑,我们可以确定 安全通信 的以下理想属性。

保密性。只有发送者和预期接收者能够理解传输消息的内容。由于窃听者可能会拦截消息,这就必须对消息进行某种形式的**加密**,使得拦截者无法理解被截获的消息。保密性可能是“安全通信”一词最常被理解的含义。我们将在 第8.2节 学习加密和解密数据的密码学技术。

消息完整性。Alice 和 Bob 想确保他们通信的内容在传输过程中不会被恶意或意外地篡改。可以利用我们在可靠传输和数据链路协议中遇到的校验和技术扩展来提供消息完整性。我们将在 第8.3节 研究消息完整性。

端点认证。发送者和接收者都应能确认通信另一方的身份——确认对方确实是他们所声称的身份。面对面的人际交流可以通过视觉识别轻松解决这个问题。而当通信实体通过看不见对方的媒介交换消息时,认证就不那么简单了。当用户想访问邮箱时,邮件服务器如何验证该用户确实是其声称的人?我们将在 第8.4节 研究端点认证。

操作安全。如今几乎所有组织(公司、大学等)都连接到公共互联网,因此其网络有可能被攻破。攻击者可能试图向网络主机植入蠕虫,窃取公司机密,绘制内部网络拓扑,发动拒绝服务(DoS)攻击。我们将在 第8.9节 看到防火墙和入侵检测系统等操作设备如何用于抵御针对组织网络的攻击。防火墙置于组织网络和公共网络之间,控制进出网络的数据包访问。入侵检测系统进行“深度数据包检测”,警告网络管理员可疑活动。

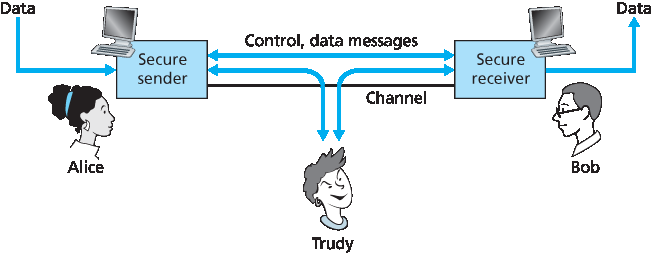

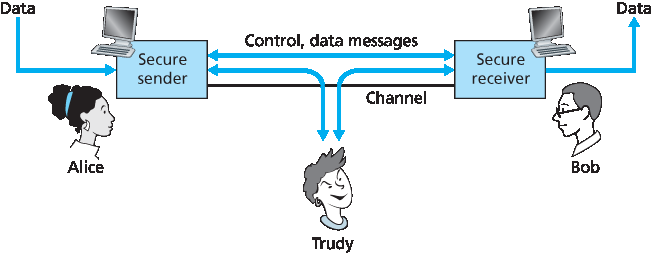

明确了网络安全的含义后,接下来让我们考虑入侵者可能获得哪些信息,以及入侵者可能采取哪些行动。图8.1 展示了该场景。发送者 Alice 希望将数据发送给接收者 Bob。为了安全交换数据,同时满足保密性、端点认证和消息完整性的要求,Alice 和 Bob 会交换控制消息和数据消息(就像 TCP 发送者和接收者交换控制段和数据段一样)。

图8.1 发送者、接收者与入侵者(Alice、Bob 和 Trudy)

这些消息全部或部分通常会被加密。如 第1.6节 所述,入侵者可能进行以下行为:

窃听——嗅探并记录信道上的控制和数据消息。

修改、插入或删除消息或消息内容。

正如我们将看到的,除非采取适当的对策,否则这些能力使入侵者能发起各种安全攻击:窃听通信(可能窃取密码和数据)、冒充其他实体、劫持正在进行的会话、通过超载系统资源拒绝合法用户服务等。CERT协调中心维护了一份攻击报告汇总 [CERT 2016]。

既然确认了互联网中确实存在真实威胁,那么互联网中需要安全通信的“Alice”和“Bob”对应的实体是什么?当然,Bob 和 Alice 可能是两个端系统上的真实用户,例如真正的 Alice 和 Bob,他们想交换安全邮件。他们也可能是电子商务交易的参与者。例如,真实的 Bob 可能想安全地将信用卡号传输给Web服务器以购买商品。同样,真实的 Alice 可能想在线与其银行交互。需要安全通信的双方也可能是网络基础设施的一部分。回想域名系统(DNS,见 第2.4节)或交换路由信息的路由守护进程(见 第5章)需要双方安全通信。网络管理应用也是如此,我们在 第5章 讨论过。能够主动干扰DNS查询(如 第2.4节 所述)、路由计算 [RFC 4272] 或网络管理功能 [RFC 3414] 的入侵者,可能会在互联网中制造混乱。

既然已经建立了框架、一些重要定义以及网络安全的必要性,接下来让我们深入研究密码学。虽然密码学在提供保密性方面的作用显而易见,但我们很快会看到,它在提供端点认证和消息完整性方面也至关重要——使密码学成为网络安全的基石。

Let’s begin our study of network security by returning to our lovers, Alice and Bob, who want to communicate “securely.” What precisely does this mean? Certainly, Alice wants only Bob to be able to understand a message that she has sent, even though they are communicating over an insecure medium where an intruder (Trudy, the intruder) may intercept whatever is transmitted from Alice to Bob. Bob also wants to be sure that the message he receives from Alice was indeed sent by Alice, and Alice wants to make sure that the person with whom she is communicating is indeed Bob. Alice and Bob also want to make sure that the contents of their messages have not been altered in transit. They also want to be assured that they can communicate in the first place (i.e., that no one denies them access to the resources needed to communicate). Given these considerations, we can identify the following desirable properties of secure communication.

Confidentiality. Only the sender and intended receiver should be able to understand the contents of the transmitted message. Because eavesdroppers may intercept the message, this necessarily requires that the message be somehow encrypted so that an intercepted message cannot be understood by an interceptor. This aspect of confidentiality is probably the most commonly perceived meaning of the term secure communication. We’ll study cryptographic techniques for encrypting and decrypting data in Section 8.2.

Message integrity. Alice and Bob want to ensure that the content of their communication is not altered, either maliciously or by accident, in transit. Extensions to the checksumming techniques that we encountered in reliable transport and data link protocols can be used to provide such message integrity. We will study message integrity in Section 8.3.

End-point authentication. Both the sender and receiver should be able to confirm the identity of the other party involved in the communication—to confirm that the other party is indeed who or what they claim to be. Face-to-face human communication solves this problem easily by visual recognition. When communicating entities exchange messages over a medium where they cannot see the other party, authentication is not so simple. When a user wants to access an inbox, how does the mail server verify that the user is the person he or she claims to be? We study end-point

authentication in Section 8.4. - Operational security. Almost all organizations (companies, universities, and so on) today have networks that are attached to the public Internet. These networks therefore can potentially be compromised. Attackers can attempt to deposit worms into the hosts in the network, obtain corporate secrets, map the internal network configurations, and launch DoS attacks. We’ll see in Section 8.9 that operational devices such as firewalls and intrusion detection systems are used to counter attacks against an organization’s network. A firewall sits between the organization’s network and the public network, controlling packet access to and from the network. An intrusion detection system performs “deep packet inspection,” alerting the network administrators about suspicious activity.

Having established what we mean by network security, let’s next consider exactly what information an intruder may have access to, and what actions can be taken by the intruder. Figure 8.1 illustrates the scenario. Alice, the sender, wants to send data to Bob, the receiver. In order to exchange data securely, while meeting the requirements of confidentiality, end-point authentication, and message integrity, Alice and Bob will exchange control messages and data messages (in much the same way that TCP senders and receivers exchange control segments and data segments).

Figure 8.1 Sender, receiver, and intruder (Alice, Bob, and Trudy)

All or some of these messages will typically be encrypted. As discussed in Section 1.6, an intruder can potentially perform

eavesdropping—sniffing and recording control and data messages on the channel.

modification, insertion, or deletion of messages or message content.

As we’ll see, unless appropriate countermeasures are taken, these capabilities allow an intruder to mount a wide variety of security attacks: snooping on communication (possibly stealing passwords and data), impersonating another entity, hijacking an ongoing session, denying service to legitimate network users by overloading system resources, and so on. A summary of reported attacks is maintained at the CERT Coordination Center [CERT 2016].

Having established that there are indeed real threats loose in the Internet, what are the Internet equivalents of Alice and Bob, our friends who need to communicate securely? Certainly, Bob and Alice might be human users at two end systems, for example, a real Alice and a real Bob who really do want to exchange secure e-mail. They might also be participants in an electronic commerce transaction. For example, a real Bob might want to transfer his credit card number securely to a Web server to purchase an item online. Similarly, a real Alice might want to interact with her bank online. The parties needing secure communication might themselves also be part of the network infrastructure. Recall that the domain name system (DNS, see Section 2.4) or routing daemons that exchange routing information (see Chapter 5) require secure communication between two parties. The same is true for network management applications, a topic we examined in Chapter 5). An intruder that could actively interfere with DNS lookups (as discussed in Section 2.4), routing computations [RFC 4272], or network management functions [RFC 3414] could wreak havoc in the Internet.

Having now established the framework, a few of the most important definitions, and the need for network security, let us next delve into cryptography. While the use of cryptography in providing confidentiality is self-evident, we’ll see shortly that it is also central to providing end-point authentication and message integrity—making cryptography a cornerstone of network security.