7.7 蜂窝网络中的移动性管理#

7.7 Managing Mobility in Cellular Networks

在我们考察了IP网络中如何管理移动性之后,现在让我们将注意力转向在支持移动性方面历史更为悠久的网络——蜂窝电话网络。尽管我们在 第7.4节 中聚焦于蜂窝网络中的首跳无线链路,但在这里我们将聚焦于移动性,并以GSM蜂窝网络为案例研究 [Goodman 1997; Mouly 1992; Scourias 2012; Kaaranen 2001; Korhonen 2003; Turner 2012],因为它是一种成熟且被广泛部署的技术。3G和4G网络中的移动性在原理上与GSM所使用的类似。就像在移动IP的案例中一样,我们会看到在 第7.5节 中所识别的一些基本原理也被体现于GSM的网络架构中。

与移动IP类似,GSM采用了间接路由的方法(见 第7.5.2节),首先将通信方的呼叫路由到移动用户的归属网络,再从那里转发至访问网络。在GSM术语中,移动用户的归属网络被称为移动用户的 归属公共陆地移动网络(home public land mobile network,home PLMN)。鉴于PLMN这一缩写有些拗口,并且为了避免缩写字母的“汤”,我们将在后文中将GSM的home PLMN简称为 归属网络。归属网络是与移动用户签约的蜂窝服务提供商(即向该用户收取月度蜂窝服务费用的提供商)。而 访问PLMN,我们将在下文中简称为 访问网络,是指当前移动用户所处的网络。

与移动IP的情形一样,归属网络与访问网络承担着截然不同的职责。

归属网络维护一个被称为 归属位置寄存器(HLR) 的数据库,该数据库中包含了每一位用户的永久手机号码以及订阅者的配置文件信息。重要的是,HLR还包含了这些用户当前位置信息。也就是说,如果某个移动用户当前正在另一个运营商的蜂窝网络中漫游,HLR中将包含足够的信息(通过一个稍后将要介绍的过程)以获取一个访问网络中的地址,从而使得对该移动用户的呼叫能够被正确路由。正如我们将看到的,归属网络中的一个特殊交换设备,被称为 网关移动服务交换中心(GMSC),会在通信方向移动用户发起呼叫时被联系到。再次出于避免缩写堆砌的考虑,我们将在此将GMSC称为更具描述性的术语:归属MSC。

访问网络维护一个被称为 访问者位置寄存器(VLR) 的数据库。VLR为当前处于该VLR所服务网络区域中的每个移动用户保存一条记录。因此,VLR中的记录会随着移动用户进入或离开该网络而不断增减。VLR通常与移动交换中心(MSC)共址,后者负责协调与访问网络相关的呼叫建立过程。

在实际应用中,某个提供商的蜂窝网络既可能作为其用户的归属网络,也可能作为其他签约于不同蜂窝提供商的移动用户的访问网络。

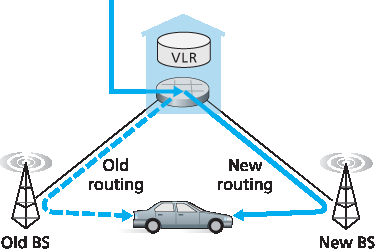

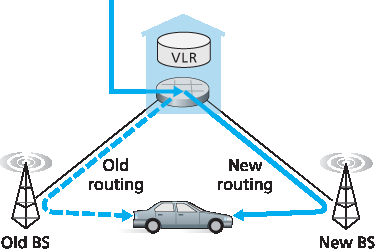

图 7.30 向移动用户拨打电话:间接路由

Having examined how mobility is managed in IP networks, let’s now turn our attention to networks with an even longer history of supporting mobility—cellular telephony networks. Whereas we focused on the first-hop wireless link in cellular networks in Section 7.4, we’ll focus here on mobility, using the GSM cellular network [Goodman 1997; Mouly 1992; Scourias 2012; Kaaranen 2001; Korhonen 2003; Turner 2012] as our case study, since it is a mature and widely deployed technology. Mobility in 3G and 4G networks is similar in principle to that used in GSM. As in the case of mobile IP, we’ll see that a number of the fundamental principles we identified in Section 7.5 are embodied in GSM’s network architecture.

Like mobile IP, GSM adopts an indirect routing approach (see Section 7.5.2), first routing the correspondent’s call to the mobile user’s home network and from there to the visited network. In GSM terminology, the mobile users’s home network is referred to as the mobile user’s home public land mobile network (home PLMN). Since the PLMN acronym is a bit of a mouthful, and mindful of our quest to avoid an alphabet soup of acronyms, we’ll refer to the GSM home PLMN simply as the home network. The home network is the cellular provider with which the mobile user has a subscription (i.e., the provider that bills the user for monthly cellular service). The visited PLMN, which we’ll refer to simply as the visited network, is the network in which the mobile user is currently residing.

As in the case of mobile IP, the responsibilities of the home and visited networks are quite different.

The home network maintains a database known as the home location register (HLR), which contains the permanent cell phone number and subscriber profile information for each of its subscribers. Importantly, the HLR also contains information about the current locations of these subscribers. That is, if a mobile user is currently roaming in another provider’s cellular network, the HLR contains enough information to obtain (via a process we’ll describe shortly) an address in the visited network to which a call to the mobile user should be routed. As we’ll see, a special switch in the home network, known as the Gateway Mobile services Switching Center (GMSC) is contacted by a correspondent when a call is placed to a mobile user. Again, in our quest to avoid an alphabet soup of acronyms, we’ll refer to the GMSC here by a more descriptive term, home MSC.

The visited network maintains a database known as the visitor location register (VLR). The VLR contains an entry for each mobile user that is currently in the portion of the network served by the VLR. VLR entries thus come and go as mobile users enter and leave the network. A VLR is usually co-located with the mobile switching center (MSC) that coordinates the setup of a call to and from the visited network.

In practice, a provider’s cellular network will serve as a home network for its subscribers and as a visited network for mobile users whose subscription is with a different cellular provider.

Figure 7.30 Placing a call to a mobile user: Indirect routing

7.7.1 向移动用户路由呼叫#

7.7.1 Routing Calls to a Mobile User

我们现在可以描述如何向处于访问网络中的GSM移动用户发起呼叫了。我们将在下文中考虑一个简单的示例;更复杂的场景可以参考 [Mouly 1992]。如 图 7.30 所示,步骤如下:

通信方拨打移动用户的电话号码。该号码本身并不指向某条具体的电话线路或地理位置(毕竟,电话号码是固定的,而用户是移动的!)。号码中的前缀数字足以在全球范围内识别出该移动用户的归属网络。呼叫从通信方通过PSTN(公共交换电话网络)路由至移动用户归属网络中的归属MSC。这是呼叫的第一跳。

归属MSC接收到该呼叫后,会向HLR发起查询,以确定移动用户的当前位置。在最简单的情况下,HLR返回 移动台漫游号码(MSRN),我们将在此称之为 漫游号码。注意,这个号码不同于移动用户的永久电话号码,后者与移动用户的归属网络关联。漫游号码是临时的:当移动用户进入某个访问网络时,会被临时分配该号码。漫游号码的作用类似于移动IP中的转交地址(COA),并且与COA一样,对通信方和移动用户来说是不可见的。如果HLR中没有该漫游号码,它会返回访问网络中VLR的地址。在这种情况下(未在 图 7.30 中展示),归属MSC需要查询该VLR,以获得该移动节点的漫游号码。但是,HLR最初是如何获得漫游号码或VLR地址的呢?当移动用户移动到另一个访问网络时,这些值又会发生什么变化?我们将很快探讨这些关键问题。

获得漫游号码后,归属MSC通过网络建立呼叫的第二跳,连接至访问网络中的MSC。呼叫过程由通信方开始,先路由至归属MSC,再从归属MSC路由至访问MSC,最后路由至为该移动用户提供服务的基站,呼叫由此完成。

在步骤2中尚未解决的问题是HLR如何获得有关移动用户位置的信息。当移动电话开机或进入由新VLR覆盖的访问网络区域时,移动设备必须在访问网络中注册。该过程通过移动设备与VLR之间的信令消息交换完成。访问网络中的VLR随后会向该移动用户的HLR发送位置更新请求消息。该消息会告知HLR移动用户的漫游号码,或者VLR的地址(稍后可以通过查询该地址来获取移动号码)。在此信息交换过程中,VLR还会从HLR中获取该移动用户的订阅信息,并确定访问网络应为该用户提供哪些服务(如果有的话)。

We’re now in a position to describe how a call is placed to a mobile GSM user in a visited network. We’ll consider a simple example below; more complex scenarios are described in [Mouly 1992]. The steps, as illustrated in Figure 7.30, are as follows:

The correspondent dials the mobile user’s phone number. This number itself does not refer to a particular telephone line or location (after all, the phone number is fixed and the user is mobile!). The leading digits in the number are sufficient to globally identify the mobile’s home network. The call is routed from the correspondent through the PSTN to the home MSC in the mobile’s home network. This is the first leg of the call.

The home MSC receives the call and interrogates the HLR to determine the location of the mobile user. In the simplest case, the HLR returns the mobile station roaming number (MSRN), which we will refer to as the roaming number. Note that this number is different from the mobile’s permanent phone number, which is associated with the mobile’s home network. The roaming number is ephemeral: It is temporarily assigned to a mobile when it enters a visited network. The roaming number serves a role similar to that of the care-of address in mobile IP and, like the COA, is invisible to the correspondent and the mobile. If HLR does not have the roaming number, it returns the address of the VLR in the visited network. In this case (not shown in Figure 7.30), the home MSC will need to query the VLR to obtain the roaming number of the mobile node. But how does the HLR get the roaming number or the VLR address in the first place? What happens to these values when the mobile user moves to another visited network? We’ll consider these important questions shortly.

Given the roaming number, the home MSC sets up the second leg of the call through the network to the MSC in the visited network. The call is completed, being routed from the correspondent to the home MSC, and from there to the visited MSC, and from there to the base station serving the mobile user.

An unresolved question in step 2 is how the HLR obtains information about the location of the mobile user. When a mobile telephone is switched on or enters a part of a visited network that is covered by a new VLR, the mobile must register with the visited network. This is done through the exchange of signaling messages between the mobile and the VLR. The visited VLR, in turn, sends a location update request message to the mobile’s HLR. This message informs the HLR of either the roaming number at which the mobile can be contacted, or the address of the VLR (which can then later be queried to obtain the mobile number). As part of this exchange, the VLR also obtains subscriber information from the HLR about the mobile and determines what services (if any) should be accorded the mobile user by the visited network.

7.7.2 GSM中的切换(Handoffs)#

7.7.2 Handoffs in GSM

当移动台在通话过程中从一个基站切换到另一个基站时,就发生了 切换(handoff)。如 图 7.31 所示,在切换之前,移动用户的通话通过一个基站(我们称之为旧基站)路由到移动用户;切换之后,通话则通过另一个基站(我们称之为新基站)路由到移动用户。请注意,基站之间的切换不仅意味着移动设备与新基站之间的收发转换,还包括正在进行的通话在网络内部的某个交换点上重新路由至新基站。我们最初假设旧基站与新基站隶属于同一个MSC,并且重新路由发生在该MSC处。

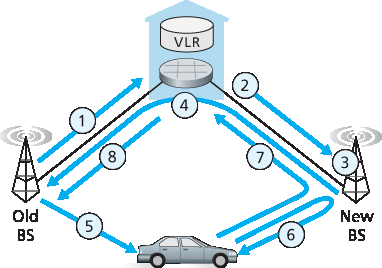

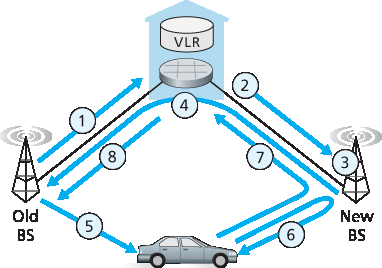

图 7.31 同一MSC下基站之间的切换场景

发生切换的原因可能有多个,包括(1)当前基站与移动台之间的信号恶化到通话可能被中断的程度,以及(2)某个小区可能过载,正在处理大量通话。通过将移动台切换到负载较轻的邻近小区可以缓解这种拥塞。

在与某个基站关联期间,移动设备会周期性地测量来自其当前基站的信标信号强度,以及其能够“听到”的邻近基站的信标信号强度。这些测量结果每秒报告一次或两次给当前基站。GSM中的切换由旧基站根据这些测量值、邻近小区中移动设备的当前负载以及其他因素发起 [Mouly 1992]。GSM标准并未规定基站用于决定是否执行切换的具体算法。

图 7.32 展示了基站决定切换移动用户时涉及的步骤:

旧基站(BS)通知访问MSC即将执行切换,并告知移动用户将切换至的新基站(或一组可能的新基站)。

访问MSC发起到新基站的路径建立,分配所需资源以承载重新路由的通话,并向新基站发出即将进行切换的信号。

新基站为移动用户分配并激活一个无线信道。

新基站向访问MSC和旧基站发出信号,表示访问MSC与新基站之间的路径已建立,应通知移动用户即将进行切换。新基站还提供移动用户与其关联所需的全部信息。

图 7.32 同一MSC下基站间切换的各个步骤

移动用户被告知应执行切换。注意,在此之前,移动用户对网络为切换所做的准备(例如,在新基站分配信道、建立访问MSC到新基站的路径)毫不知情。

移动设备与新基站交换一个或多个消息,以完全激活新基站中的新信道。

移动设备向新基站发送“切换完成”消息,该消息随后转发至访问MSC。访问MSC随后通过新基站将正在进行的通话重新路由至移动用户。

分配给旧基站路径的资源随后被释放。

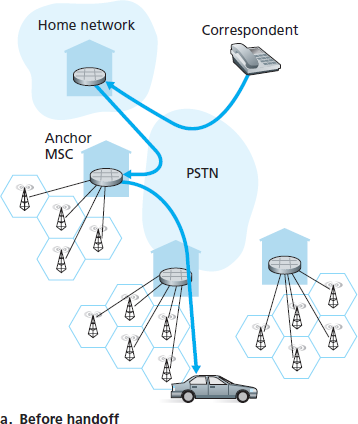

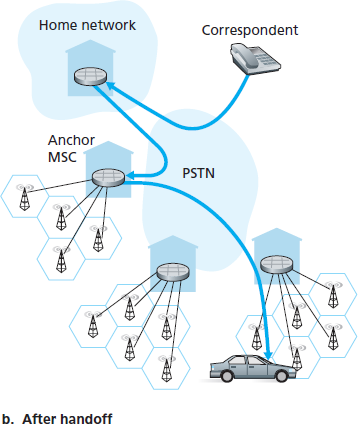

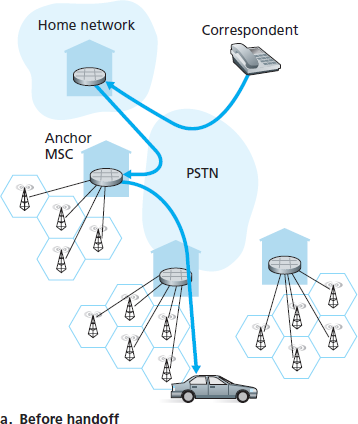

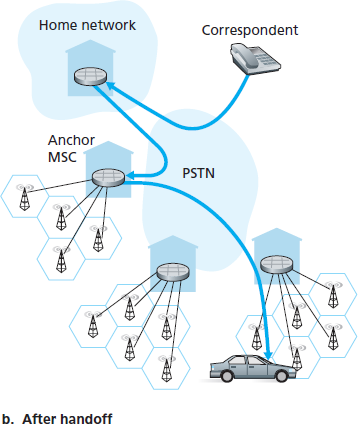

让我们通过考虑以下情况来结束对切换的讨论:当移动用户移动到一个与旧基站关联的MSC不同的新基站时会发生什么?当这种跨MSC切换多次发生时又会发生什么?如 图 7.33 所示,GSM定义了 锚定MSC(anchor MSC) 的概念。锚定MSC是移动用户首次发起通话时所访问的MSC;在整个通话期间,锚定MSC保持不变。无论通话期间发生多少次跨MSC转移,通话总是从归属MSC路由至锚定MSC,再从锚定MSC路由至当前移动用户所在的访问MSC。当移动用户从一个MSC的覆盖区域移动到另一个MSC的覆盖区域时,正在进行的通话就会从锚定MSC重新路由到包含新基站的新访问MSC。因此,在任何时刻,通信路径中最多存在三个MSC(归属MSC、锚定MSC和访问MSC)。图 7.33 展示了移动用户在多个MSC间路由通话的情况。

图 7.33 通过锚定MSC重新路由

表 7.2 移动IP与GSM移动性的共通性

GSM元素 |

对GSM元素的说明 |

移动IP元素 |

归属系统 |

移动用户永久电话号码所属的网络。 |

归属网络 |

网关移动交换中心(或简称归属MSC)、归属位置寄存器(HLR) |

归属MSC:用于获取可路由地址的联系点。HLR:归属系统中的数据库,包含永久电话号码、用户资料、当前位置信息、订阅信息。 |

归属代理(home agent) |

访问系统 |

除归属系统以外,移动用户当前所在的网络。 |

访问网络 |

访问移动交换中心、访问位置寄存器(VLR) |

访问MSC:负责在其管辖的小区中发起和接收与移动节点的通话。VLR:访问系统中的临时数据库条目,包含每位访问移动用户的订阅信息。 |

外部代理(foreign agent) |

移动台漫游号码(MSRN)或简称漫游号码 |

从归属MSC到访问MSC之间通话段的可路由地址,对通信方和移动用户均不可见。 |

转交地址(care-of address) |

除了维持从锚定MSC到当前MSC的一跳路径外,还有一种替代方法是简单地将移动用户访问过的MSC进行“链式连接”,即每次移动用户进入新MSC时,由旧MSC将正在进行的通话转发至新MSC。这种MSC链式连接的方式在IS-41蜂窝网络中确实存在,且可选地通过路径最小化步骤移除锚定MSC与当前访问MSC之间的MSC节点 [Lin 2001]。

让我们通过对GSM与移动IP中移动性管理的比较来结束本节讨论。如 表 7.2 所示,虽然IP和蜂窝网络在许多方面存在根本差异,但它们在处理移动性方面却拥有许多令人惊讶的功能共通性和总体方法上的相似之处。

A handoff occurs when a mobile station changes its association from one base station to another during a call. As shown in Figure 7.31, a mobile’s call is initially (before handoff) routed to the mobile through one base station (which we’ll refer to as the old base station), and after handoff is routed to the mobile through another base station (which we’ll refer to as the new base station). Note that a handoff between base stations results not only in the mobile transmitting/receiving to/from a new base station, but also in the rerouting of the ongoing call from a switching point within the network to the new base station. Let’s initially assume that the old and new base stations share the same MSC, and that the rerouting occurs at this MSC.

Figure 7.31 Handoff scenario between base stations with a common MSC

There may be several reasons for handoff to occur, including (1) the signal between the current base station and the mobile may have deteriorated to such an extent that the call is in danger of being dropped, and (2) a cell may have become overloaded, handling a large number of calls. This congestion may be alleviated by handing off mobiles to less congested nearby cells.

While it is associated with a base station, a mobile periodically measures the strength of a beacon signal from its current base station as well as beacon signals from nearby base stations that it can “hear.” These measurements are reported once or twice a second to the mobile’s current base station. Handoff in GSM is initiated by the old base station based on these measurements, the current loads of mobiles in nearby cells, and other factors [Mouly 1992]. The GSM standard does not specify the specific algorithm to be used by a base station to determine whether or not to perform handoff.

Figure 7.32 illustrates the steps involved when a base station does decide to hand off a mobile user:

The old base station (BS) informs the visited MSC that a handoff is to be performed and the BS (or possible set of BSs) to which the mobile is to be handed off.

The visited MSC initiates path setup to the new BS, allocating the resources needed to carry the rerouted call, and signaling the new BS that a handoff is about to occur.

The new BS allocates and activates a radio channel for use by the mobile.

The new BS signals back to the visited MSC and the old BS that the visited-MSC-to-new-BS path has been established and that the mobile should beinformed of the impending handoff. The new BS provides all of the information that the mobile will need to associate with the new BS.

Figure 7.32 Steps in accomplishing a handoff between base stations with a common MSC

The mobile is informed that it should perform a handoff. Note that up until this point, the mobile has been blissfully unaware that the network has been laying the groundwork (e.g., allocating a channel in the new BS and allocating a path from the visited MSC to the new BS) for a handoff.

The mobile and the new BS exchange one or more messages to fully activate the new channel in the new BS.

The mobile sends a handoff complete message to the new BS, which is forwarded up to the visited MSC. The visited MSC then reroutes the ongoing call to the mobile via the new BS.

The resources allocated along the path to the old BS are then released.

Let’s conclude our discussion of handoff by considering what happens when the mobile moves to a BS that is associated with a different MSC than the old BS, and what happens when this inter-MSC handoff occurs more than once. As shown in Figure 7.33, GSM defines the notion of an anchor MSC. The anchor MSC is the MSC visited by the mobile when a call first begins; the anchor MSC thus remains unchanged during the call. Throughout the call’s duration and regardless of the number of inter-MSC transfers performed by the mobile, the call is routed from the home MSC to the anchor MSC, and then from the anchor MSC to the visited MSC where the mobile is currently located. When a mobile moves from the coverage area of one MSC to another, the ongoing call is rerouted from the anchor MSC to the new visited MSC containing the new base station. Thus, at all times there are at most three MSCs (the home MSC, the anchor MSC, and the visited MSC) between the correspondent and the mobile. Figure 7.33 illustrates the routing of a call among the MSCs visited by a mobile user.

Figure 7.33 Rerouting via the anchor MSC

Table 7.2 Commonalities between mobile IP and GSM mobility

GSM element |

Comment on GSM element |

Mobile IP element |

Home system |

Network to which the mobile user’s permanent phone number belongs. |

Home network |

Gateway mobile switching center or simply home MSC, Home location register (HLR) |

Home MSC: point of contact to obtain routable address of mobile user. HLR: database in home system containing permanent phone number, profile information, current location of mobile user, subscription information. |

Home agent |

Visited system |

Network other than home system where mobile user is currently residing. |

Visited network |

Visited mobile services switching center, Visitor location register (VLR) |

Visited MSC: responsible for setting up calls to/from mobile nodes in cells associated with MSC. VLR: temporary database entry in visited system, containing subscription information for each visiting mobile user. |

Foreign agent |

Mobile station roaming number (MSRN) or simply roaming number |

Routable address for telephone call segment between home MSC and visited MSC, visible to neither the mobile nor the correspondent. |

Care-of addressed |

Rather than maintaining a single MSC hop from the anchor MSC to the current MSC, an alternative approach would have been to simply chain the MSCs visited by the mobile, having an old MSC forward the ongoing call to the new MSC each time the mobile moves to a new MSC. Such MSC chaining can in fact occur in IS-41 cellular networks, with an optional path minimization step to remove MSCs between the anchor MSC and the current visited MSC [Lin 2001].

Let’s wrap up our discussion of GSM mobility management with a comparison of mobility management in GSM and Mobile IP. The comparison in Table 7.2 indicates that although IP and cellular networks are fundamentally different in many ways, they share a surprising number of common functional elements and overall approaches in handling mobility.