7.1 简介#

7.1 Introduction

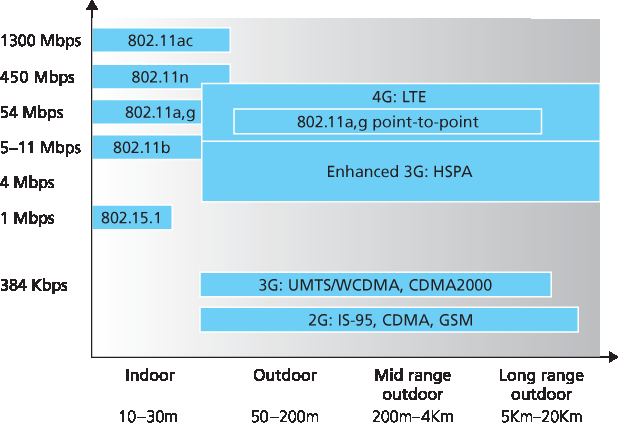

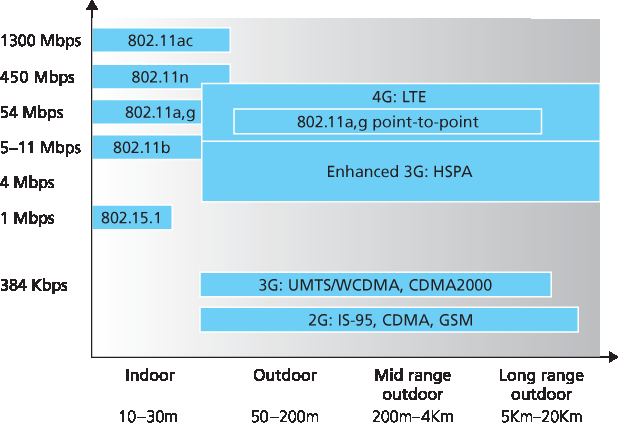

图 7.1 展示了我们将要探讨无线数据通信与移动性话题的背景环境。我们将从足够广泛的层面展开讨论,以涵盖多种网络,包括 IEEE 802.11 等无线局域网和 4G 网络等蜂窝网络;随后我们会在本章后续部分深入讨论具体的无线体系结构。在无线网络中,我们可以识别出以下元素:

无线主机。与有线网络中的主机一样,主机是运行应用程序的端系统设备。 无线主机 可以是笔记本电脑、平板电脑、智能手机或台式机。这些主机本身可以是移动的,也可以是静止的。

图 7.1 无线网络的组成元素

无线链路。主机通过 无线通信链路 连接到基站(定义如下)或另一个无线主机。不同的无线链路技术具有不同的传输速率,并能传输不同的距离。图 7.2 显示了一些主流无线网络标准的两个关键特征(覆盖范围和链路速率)。(该图仅用于粗略说明这些特性。例如,其中某些类型的网络仍在部署阶段,某些链路速率可能会因为距离、信道条件和无线网络中的用户数量而高于或低于图中所示的值。)我们将在本章前半部分介绍这些标准;在 第 7.2 节 中,我们还将探讨其他无线链路特性(如比特错误率及其成因)。

在 图 7.1 中,无线链路将处于网络边缘的无线主机连接到更大的网络基础设施。我们需要补充的是,在网络内部也有可能使用无线链路连接路由器、交换机以及其他网络设备。但在本章中,我们将重点关注在网络边缘使用无线通信,因为许多令人兴奋的技术挑战和大部分的增长都发生在这里。

图 7.2 所选无线网络标准的链路特性

基站。 基站 是无线网络基础设施中的关键部分。与无线主机和无线链路不同,基站在有线网络中没有明显的对应物。基站负责向与其关联的无线主机发送和接收数据(如分组)。一个基站通常还负责协调与其关联的多个无线主机的传输。当我们说某个无线主机“关联”到某个基站时,我们的意思是:(1) 主机处于该基站的无线通信范围内,并且 (2) 主机通过该基站中继其与更大网络之间的数据。蜂窝网络中的 小区塔 和 802.11 无线局域网中的 接入点 都是基站的例子。

在 图 7.1 中,基站连接到更大的网络(例如互联网、企业网络或电话网络),因此它在无线主机与其通信的外部世界之间起到链路层中继的作用。

与基站关联的主机通常被认为是运行于 基础设施模式 中,因为所有传统的网络服务(如地址分配和路由)都是由主机通过基站连接到的网络提供的。而在 自组织网络 中,无线主机无法连接到这样的基础设施。在没有基础设施的情况下,主机本身必须提供诸如路由、地址分配、类 DNS 名称解析等服务。

案例历史

公共 WiFi 接入:路灯杆上的热点即将到来?

WiFi 热点——用户可以访问 802.11 无线的公共位置——在全球的酒店、机场和咖啡馆越来越普遍。大多数大学校园提供无处不在的无线接入,如今很难找到不提供无线互联网接入的酒店。

过去十年中,一些城市设计、部署并运营了市政 WiFi 网络。将 WiFi 接入作为公共服务(类似街灯)提供给社区以弥合数字鸿沟并促进经济发展,这一愿景具有强大吸引力。包括费城、多伦多、香港、明尼阿波利斯、伦敦和奥克兰在内的许多城市已经制定或部分实施了提供城市范围无线接入的计划。费城的目标是“将费城变为全国最大的 WiFi 热点,并帮助提升教育、弥合数字鸿沟、增强社区发展并降低政府成本”。这个雄心勃勃的项目——由市政府、Wireless Philadelphia(一个非营利机构)以及互联网服务提供商 Earthlink 合作建成——在街灯杆臂和交通控制设备上部署了 802.11b 热点,覆盖了城市的 80%。但由于财政和运营问题,该网络于 2008 年出售给了一组私人投资者,并在 2010 年再次回售给市政府。其他城市如明尼阿波利斯、多伦多、香港和奥克兰则在较小规模的项目中取得了一定成功。

由于 802.11 网络运行在无需许可的频谱中(因此可以在无需购买昂贵频谱使用权的情况下部署),这似乎使其在经济上更具吸引力。然而,802.11 接入点(见 第 7.3 节)的覆盖范围远短于 4G 蜂窝基站(见 第 7.4 节),这就要求部署更多的终端以覆盖相同的地理区域。相对而言,提供互联网接入的蜂窝数据网络运行在有许可的频谱中,运营商需支付数十亿美元以获得频谱使用权,因此蜂窝数据网络更像是商业项目而非市政工程。

当移动主机超出一个基站的范围并进入另一个基站的范围时,它会改变其在更大网络中的连接点(即更换所关联的基站)——这一过程称为 切换(handoff)。这种移动性带来了许多技术挑战。如果主机可以移动,我们该如何定位其在网络中的当前位置,以便向其转发数据?在主机可能处于多个位置的情况下,地址如何分配?如果主机在 TCP 连接或电话通话过程中移动,数据如何路由以维持连接不中断?这些问题,以及(非常多的)其他问题,使无线和移动网络成为一个令人兴奋的研究领域。

网络基础设施。这是无线主机希望与之通信的更大网络。

在介绍完无线网络的“组成部分”后,我们需要指出,这些组成部分可以以多种方式组合,从而形成不同类型的无线网络。在阅读本章或进一步学习无线网络时,你可能会发现下面的无线网络分类法非常有用。在最高层次上,我们可以根据两个标准对无线网络进行分类:(i) 无线网络中的分组是跨越一个无线跳数还是多个无线跳数;(ii) 网络中是否存在如基站一样的基础设施:

单跳、基于基础设施。这类网络中存在一个连接到更大有线网络(如互联网)的基站。此外,所有通信都发生在该基站与无线主机之间的单个无线跳上。你在教室、咖啡馆或图书馆使用的 802.11 网络,以及我们将要学习的 4G LTE 数据网络,均属于这一类别。我们日常接触的无线网络绝大多数是单跳、基础设施型网络。

单跳、无基础设施。这类网络中不存在连接到有线网络的基站。然而,如我们将看到的,网络中某个节点可能负责协调其他节点的传输。Bluetooth 网络(连接诸如键盘、音箱和耳机等小型无线设备,我们将在 第 7.3.6 节 中学习)和 802.11 的自组织模式均属于单跳、无基础设施网络。

多跳、基于基础设施。在这类网络中,存在一个连接到更大网络的基站。但有些无线节点可能需要通过其他无线节点中继其通信,以通过基站进行通信。某些无线传感器网络和所谓的 无线网状网络 属于这一类。

多跳、无基础设施。这类网络中没有基站,节点之间需要通过多个其他节点中继消息才能到达目的地。节点还可能是移动的,连接关系在节点之间动态变化——这种网络被称为 移动自组织网络(MANET)。如果移动节点是车辆,该网络就是 车载自组织网络(VANET)。正如你可以想象的,为这种网络开发协议具有相当大的挑战性,也是当前研究的热点之一。

在本章中,我们将主要集中讨论单跳网络,尤其是基础设施型网络。

现在,让我们更深入地探讨无线和移动网络中所面临的技术挑战。我们将从无线链路本身开始,关于移动性的讨论将延后至本章后半部分。

Figure 7.1 shows the setting in which we’ll consider the topics of wireless data communication and mobility. We’ll begin by keeping our discussion general enough to cover a wide range of networks, including both wireless LANs such as IEEE 802.11 and cellular networks such as a 4G network; we’ll drill down into a more detailed discussion of specific wireless architectures in later sections. We can identify the following elements in a wireless network:

Wireless hosts. As in the case of wired networks, hosts are the end-system devices that run applications. A wireless host might be a laptop, tablet, smartphone, or desktop computer. The hosts themselves may or may not be mobile.

Figure 7.1 Elements of a wireless network

Wireless links. A host connects to a base station (defined below) or to another wireless host through a wireless communication link. Different wireless link technologies have different transmission rates and can transmit over different distances. Figure 7.2 shows two key characteristics (coverage area and link rate) of the more popular wireless network standards. (The figure is only meant to provide a rough idea of these characteristics. For example, some of these types of networks are only now being deployed, and some link rates can increase or decrease beyond the values shown depending on distance, channel conditions, and the number of users in the wireless network.) We’ll cover these standards later in the first half of this chapter; we’ll also consider other wireless link characteristics (such as their bit error rates and the causes of bit errors) in Section 7.2.

In Figure 7.1, wireless links connect wireless hosts located at the edge of the network into the larger network infrastructure. We hasten to add that wireless links are also sometimes used within a network to connect routers, switches, and other network equipment. However, our focus in this chapter will be on the use of wireless communication at the network edge, as it is here that many of the most exciting technical challenges, and most of the growth, are occurring.

Figure 7.2 Link characteristics of selected wireless network standards

Base station. The base station is a key part of the wireless network infrastructure. Unlike the wireless host and wireless link, a base station has no obvious counterpart in a wired network. A base station is responsible for sending and receiving data (e.g., packets) to and from a wireless host that is associated with that base station. A base station will often be responsible for coordinating the transmission of multiple wireless hosts with which it is associated. When we say a wireless host is “associated” with a base station, we mean that (1) the host is within the wireless communication distance of the base station, and (2) the host uses that base station to relay data between it (the host) and the larger network. Cell towers in cellular networks and access points in 802.11 wireless LANs are examples of base stations.

In Figure 7.1, the base station is connected to the larger network (e.g., the Internet, corporate or home network, or telephone network), thus functioning as a link-layer relay between the wireless host and the rest of the world with which the host communicates.

Hosts associated with a base station are often referred to as operating in infrastructure mode, since all traditional network services (e.g., address assignment and routing) are provided by the network to which a host is connected via the base station. In ad hoc networks, wireless hosts have no such infrastructure with which to connect. In the absence of such infrastructure, the hosts themselves must provide for services such as routing, address assignment, DNS-like name translation, and more.

CASE HISTORY

PUBLIC WIFI ACCESS: COMING SOON TO A LAMP POST NEAR YOU?

WiFi hotspots—public locations where users can find 802.11 wireless access—are becoming increasingly common in hotels, airports, and cafés around the world. Most college campuses offer ubiquitous wireless access, and it’s hard to find a hotel that doesn’t offer wireless Internet access.

Over the past decade a number of cities have designed, deployed, and operated municipal WiFi networks. The vision of providing ubiquitous WiFi access to the community as a public service (much like streetlights)—helping to bridge the digital divide by providing Internet access to all citizens and to promote economic development—is compelling. Many cities around the world, including Philadelphia, Toronto, Hong Kong, Minneapolis, London, and Auckland, have plans to provide ubiquitous wireless within the city, or have already done so to varying degrees. The goal in Philadelphia was to “turn Philadelphia into the nation’s largest WiFi hotspot and help to improve education, bridge the digital divide, enhance neighborhood development, and reduce the costs of government.” The ambitious program— an agreement between the city, Wireless Philadelphia (a nonprofit entity), and the Internet Service Provider Earthlink—built an operational network of 802.11b hotspots on streetlamp pole arms and traffic control devices that covered 80 percent of the city. But financial and operational concerns caused the network to be sold to a group of private investors in 2008, who later sold the network back to the city in 2010. Other cities, such as Minneapolis, Toronto, Hong Kong, and Auckland, have had success with smaller-scale efforts.

The fact that 802.11 networks operate in the unlicensed spectrum (and hence can be deployed without purchasing expensive spectrum use rights) would seem to make them financially attractive. However, 802.11 access points (see Section 7.3) have much shorter ranges than 4G cellular base stations (see Section 7.4), requiring a larger number of deployed endpoints to cover the same geographic region. Cellular data networks providing Internet access, on the other hand, operate in the licensed spectrum. Cellular providers pay billions of dollars for spectrum access rights for their networks, making cellular data networks a business rather than municipal undertaking.

When a mobile host moves beyond the range of one base station and into the range of another, it will change its point of attachment into the larger network (i.e., change the base station with which it is associated)—a process referred to as handoff. Such mobility raises many challenging questions. If a host can move, how does one find the mobile host’s current location in the network so that data can be forwarded to that mobile host? How is addressing performed, given that a host can be in one of many possible locations? If the host moves during a TCP connection or phone call, how is data routed so that the connection continues uninterrupted? These and many (many!) other questions make wireless and mobile networking an area of exciting networking research.

Network infrastructure. This is the larger network with which a wireless host may wish to communicate.

Having discussed the “pieces” of a wireless network, we note that these pieces can be combined in many different ways to form different types of wireless networks. You may find a taxonomy of these types of wireless networks useful as you read on in this chapter, or read/learn more about wireless networks beyond this book. At the highest level we can classify wireless networks according to two criteria: (i) whether a packet in the wireless network crosses exactly one wireless hop or multiple wireless hops, and (ii) whether there is infrastructure such as a base station in the network:

Single-hop, infrastructure-based. These networks have a base station that is connected to a larger wired network (e.g., the Internet). Furthermore, all communication is between this base station and a wireless host over a single wireless hop. The 802.11 networks you use in the classroom, café, or library; and the 4G LTE data networks that we will learn about shortly all fall in this category. The vast majority of our daily interactions are with single-hop, infrastructure-based wireless networks.

Single-hop, infrastructure-less. In these networks, there is no base station that is connected to a wireless network. However, as we will see, one of the nodes in this single-hop network may coordinate the transmissions of the other nodes. Bluetooth networks (that connect small wireless devices such as keyboards, speakers, and headsets, and which we will study in Section 7.3.6) and 802.11 networks in ad hoc mode are single-hop, infrastructure-less networks.

Multi-hop, infrastructure-based. In these networks, a base station is present that is wired to the larger network. However, some wireless nodes may have to relay their communication through other wireless nodes in order to communicate via the base station. Some wireless sensor networks and so-called wireless mesh networks fall in this category.

Multi-hop, infrastructure-less. There is no base station in these networks, and nodes may have to relay messages among several other nodes in order to reach a destination. Nodes may also be mobile, with connectivity changing among nodes—a class of networks known as mobile ad hoc networks (MANETs). If the mobile nodes are vehicles, the network is a vehicular ad hoc network (VANET). As you might imagine, the development of protocols for such networks is challenging and is the subject of much ongoing research.

In this chapter, we’ll mostly confine ourselves to single-hop networks, and then mostly to infrastructure-based networks.

Let’s now dig deeper into the technical challenges that arise in wireless and mobile networks. We’ll begin by first considering the individual wireless link, deferring our discussion of mobility until later in this chapter.