2.5 对等网络应用#

2.5 Peer-to-Peer Applications

到目前为止,本章描述的应用程序——包括 Web、电子邮件和 DNS——都采用了客户端-服务器架构,并在很大程度上依赖于始终在线的基础设施服务器。回顾 第 2.1.1 节,在 P2P 架构中,几乎不依赖(或完全不依赖)始终在线的基础设施服务器。相反,一对一的间歇连接主机(称为对等方,peers)彼此直接通信。这些对等方不属于某个服务提供商,而是由用户控制的桌面电脑和笔记本电脑。

在本节中,我们将探讨一种非常自然的 P2P 应用,即将一个大文件从单个服务器分发到大量主机(称为对等方)。该文件可能是 Linux 操作系统的新版本、某个操作系统或应用程序的软件补丁、一个 MP3 音乐文件或 MPEG 视频文件。在客户端-服务器文件分发中,服务器必须向每个对等方发送一份文件副本——这给服务器带来了巨大的负担,并消耗了大量带宽。而在 P2P 文件分发中,每个对等方都可以将其接收到的文件部分重新分发给其他对等方,从而协助服务器完成分发任务。截至 2016 年,最流行的 P2P 文件分发协议是 BitTorrent。该协议最初由 Bram Cohen 开发,如今已出现许多符合 BitTorrent 协议的独立客户端,正如有许多符合 HTTP 协议的 Web 浏览器客户端一样。在本小节中,我们首先分析 P2P 架构在文件分发场景中的自我可扩展性(self-scalability),然后对 BitTorrent 协议做详细介绍,突出其最重要的特性与机制。

The applications described in this chapter thus far—including the Web, e-mail, and DNS—all employ client-server architectures with significant reliance on always-on infrastructure servers. Recall from Section 2.1.1 that with a P2P architecture, there is minimal (or no) reliance on always-on infrastructure servers. Instead, pairs of intermittently connected hosts, called peers, communicate directly with each other. The peers are not owned by a service provider, but are instead desktops and laptops controlled by users.

In this section we consider a very natural P2P application, namely, distributing a large file from a single server to a large number of hosts (called peers). The file might be a new version of the Linux operating system, a software patch for an existing operating system or application, an MP3 music file, or an MPEG video file. In client-server file distribution, the server must send a copy of the file to each of the peers—placing an enormous burden on the server and consuming a large amount of server bandwidth. In P2P file distribution, each peer can redistribute any portion of the file it has received to any other peers, thereby assisting the server in the distribution process. As of 2016, the most popular P2P file distribution protocol is BitTorrent. Originally developed by Bram Cohen, there are now many different independent BitTorrent clients conforming to the BitTorrent protocol, just as there are a number of Web browser clients that conform to the HTTP protocol. In this subsection, we first examine the self- scalability of P2P architectures in the context of file distribution. We then describe BitTorrent in some detail, highlighting its most important characteristics and features.

2.5.1 P2P 文件分发#

2.5.1 P2P File Distribution

P2P 架构的可扩展性#

Scalability of P2P Architectures

为比较客户端-服务器架构和对等网络架构,并说明 P2P 的内在自我可扩展性,我们现在为这两种架构建立一个用于将文件分发到固定对等方集合的简单定量模型。如 图 2.22 所示,服务器和对等方通过接入链路连接到互联网。设服务器接入链路的上传速率为 us,第 i 个对等方接入链路的上传速率为 ui,下载速率为 di。设要分发的文件大小为 F(以比特计),希望获得文件副本的对等方数量为 N。 分发时间 指的是将文件副本传送给所有 N 个对等方所需的时间。在下面对这两种架构分发时间的分析中,我们做一个简化(但通常准确 [Akella 2003]) 假设,即互联网核心拥有充足的带宽,意味着所有瓶颈都在接入网络中。我们还假设服务器和客户端不参与任何其他网络应用,因此他们所有的上传与下载接入带宽都可以完全用于文件分发。

图 2.22 文件分发问题示意图

首先来确定客户端-服务器架构的分发时间,记为 Dcs。在客户端-服务器架构中,没有对等方参与文件分发。我们做出以下观察:

服务器必须向每个对等方传输一份文件,因此服务器需要传输 NF 比特。由于服务器上传速率为 us,因此文件分发时间至少为 \(NF/u_s\)。

设 \(d_{min}\) 表示下载速率最慢的对等方,即 \(dmin=min{d_1,d_2,. . .,d_N}\)。下载速率最慢的对等方获取完整文件(F 比特)所需时间至少为 \(F/d_{min}\) 秒。因此最小分发时间至少为 \(F/d_{min}\)。

将上述两条观察合并,我们得到:

Dcs≥max{NFus,Fdmin}.

这就为客户端-服务器架构的最小分发时间提供了一个下界。在作业中你将被要求证明服务器可以安排其传输使该下界确实达到。因此,我们将上述下界作为实际分发时间,即:

由 (1) 可见,当 N 足够大时,客户端-服务器的分发时间为 NF/us。因此,分发时间随对等方数量 N 线性增长。例如,如果某一周对等方数量从 1,000 增加到 1,000,000,所需分发时间将增长 1,000 倍。

现在我们对 P2P 架构进行类似分析,在该架构中,每个对等方都可以协助服务器分发文件。具体来说,当对等方接收到部分文件后,可利用自身上传能力将数据重新分发给其他对等方。由于分发时间依赖于每个对等方如何将文件部分传递给其他对等方,P2P 架构的分发时间计算比客户端-服务器架构复杂。但依然可以得到一个简单的最小分发时间表达式 [Kumar 2006]。为此,我们做出以下观察:

分发开始时,只有服务器拥有完整文件。要将该文件引入对等方群体中,服务器必须至少一次将每一比特送入其接入链路。因此,最小分发时间至少为 F/us。(不同于客户端-服务器方式,服务器发出的一比特不必再发送一次,因为对等方可彼此重新分发该比特。)

与客户端-服务器架构一样,下载速率最慢的对等方无法在少于 \(F/d_{min}\) 秒内获取完整文件。因此最小分发时间至少为 \(F/d_{min}\)。

最后,系统的总上传能力为服务器上传速率加上每个对等方的上传速率,即 utotal=us+u1+⋯+uN。系统必须向 N 个对等方分发(上传) F 比特,总传输量为 NF 比特。该过程所需时间不可能少于 \(NF/u_{total}\)。因此,最小分发时间还至少为 NF/(us+u1+⋯+uN)。

将这三条观察合并,得到 P2P 的最小分发时间,记作 \(D_{P2P}\):

(2) 给出了 P2P 架构的最小分发时间下界。实际上,如果我们设想每个对等方在接收到比特后即可重新分发,则存在一种分发策略可达成此下界 [Kumar 2006]。(我们将在作业中证明该结论的特例。)现实中文件是按块(chunk)分发,而不是逐比特,(2) 是实际最小分发时间的良好近似。因此我们将其作为实际最小分发时间,即:

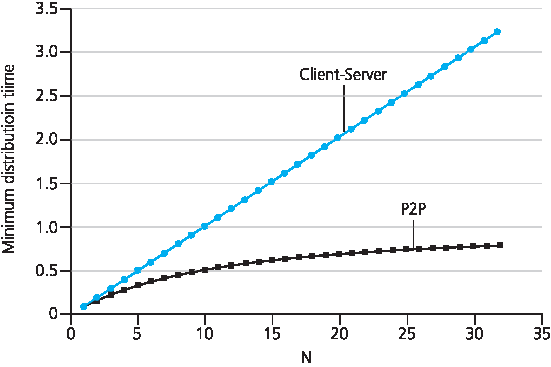

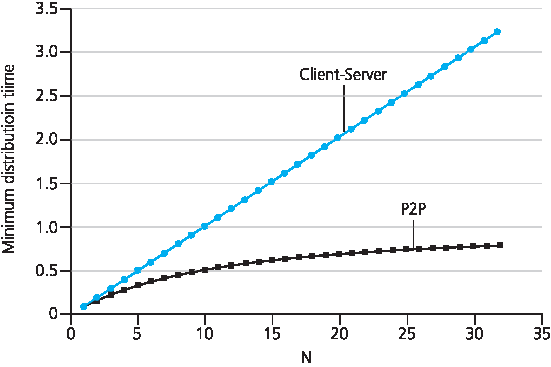

图 2.23 对比了客户端-服务器架构和 P2P 架构的最小分发时间,假设所有对等方上传速率均为 u。在 图 2.23 中,我们设 F/u=1 小时,us=10u,且 dmin≥us。即:对等方可在一小时内传输整个文件,服务器传输速率是对等方的 10 倍,并设下载速率足够高,不构成瓶颈。可见:在客户端-服务器架构中,分发时间随对等方数量线性增长且无上限。而在 P2P 架构中,最小分发时间不仅总是小于客户端-服务器架构的分发时间,而且在任意对等方数量 N 下均小于 1 小时。因此,采用 P2P 架构的应用具备自我扩展能力。这种可扩展性直接得益于对等方既是比特的消费者,也是分发者。

图 2.23 P2P 与客户端-服务器架构的分发时间

To compare client-server architectures with peer-to-peer architectures, and illustrate the inherent self- scalability of P2P, we now consider a simple quantitative model for distributing a file to a fixed set of peers for both architecture types. As shown in Figure 2.22, the server and the peers are connected to the Internet with access links. Denote the upload rate of the server’s access link by us, the upload rate of the ith peer’s access link by ui, and the download rate of the ith peer’s access link by di. Also denote the size of the file to be distributed (in bits) by F and the number of peers that want to obtain a copy of the file by N. The distribution time is the time it takes to get a copy of the file to all N peers. In our analysis of the distribution time below, for both client-server and P2P architectures, we make the simplifying (and generally accurate [Akella 2003]) assumption that the Internet core has abundant bandwidth, implying that all of the bottlenecks are in access networks. We also suppose that the server and clients are not participating in any other network applications, so that all of their upload and download access bandwidth can be fully devoted to distributing this file.

Figure 2.22 An illustrative file distribution problem

Let’s first determine the distribution time for the client-server architecture, which we denote by Dcs. In the client-server architecture, none of the peers aids in distributing the file. We make the following observations:

The server must transmit one copy of the file to each of the N peers. Thus the server must transmit NF bits. Since the server’s upload rate is us, the time to distribute the file must be at least \(NF/u_s\).

Let \(d_{min}\) denote the download rate of the peer with the lowest download rate, that is, \(dmin=min{d_1,d_p,. . .,d_N}\). The peer with the lowest download rate cannot obtain all F bits of the file in less than \(F/d_{min}\) seconds. Thus the minimum distribution time is at least \(F/d_{min}\).

Putting these two observations together, we obtain

Dcs≥max{NFus,Fdmin}.

This provides a lower bound on the minimum distribution time for the client-server architecture. In the homework problems you will be asked to show that the server can schedule its transmissions so that the lower bound is actually achieved. So let’s take this lower bound provided above as the actual distribution time, that is,

Dcs≥max{NFus,Fdmin}. (2.1)

We see from Equation 2.1 that for N large enough, the client-server distribution time is given by NF/us. Thus, the distribution time increases linearly with the number of peers N. So, for example, if the number of peers from one week to the next increases a thousand-fold from a thousand to a million, the time required to distribute the file to all peers increases by 1,000.

Let’s now go through a similar analysis for the P2P architecture, where each peer can assist the server in distributing the file. In particular, when a peer receives some file data, it can use its own upload capacity to redistribute the data to other peers. Calculating the distribution time for the P2P architecture is somewhat more complicated than for the client-server architecture, since the distribution time depends on how each peer distributes portions of the file to the other peers. Nevertheless, a simple expression for the minimal distribution time can be obtained [Kumar 2006]. To this end, we first make the following observations:

At the beginning of the distribution, only the server has the file. To get this file into the community of peers, the server must send each bit of the file at least once into its access link. Thus, the minimum distribution time is at least F/us. (Unlike the client-server scheme, a bit sent once by the server may not have to be sent by the server again, as the peers may redistribute the bit among themselves.)

As with the client-server architecture, the peer with the lowest download rate cannot obtain all F bits of the file in less than \(F/d_{min}\) seconds. Thus the minimum distribution time is at least \(F/d_{min}\).

Finally, observe that the total upload capacity of the system as a whole is equal to the upload rate of the server plus the upload rates of each of the individual peers, that is, utotal=us+u1+⋯+uN. The system must deliver (upload) F bits to each of the N peers, thus delivering a total of NF bits. This cannot be done at a rate faster than \(u_{total}\). Thus, the minimum distribution time is also at least NF/(us+u1+⋯+uN).

Putting these three observations together, we obtain the minimum distribution time for P2P, denoted by \(D_{P2P}\).

DP2P≥max{Fus,Fdmin,NFus+∑i=1Nui} (2.2)

Equation 2.2 provides a lower bound for the minimum distribution time for the P2P architecture. It turns out that if we imagine that each peer can redistribute a bit as soon as it receives the bit, then there is a redistribution scheme that actually achieves this lower bound [Kumar 2006]. (We will prove a special case of this result in the homework.) In reality, where chunks of the file are redistributed rather than individual bits, Equation 2.2 serves as a good approximation of the actual minimum distribution time. Thus, let’s take the lower bound provided by Equation 2.2 as the actual minimum distribution time, that is,

DP2P=max{Fus,Fdmin,NFus+∑i=1Nui} (2.3)

Figure 2.23 compares the minimum distribution time for the client-server and P2P architectures assuming that all peers have the same upload rate u. In Figure 2.23, we have set F/u=1 hour, us=10u, and dmin≥us. Thus, a peer can transmit the entire file in one hour, the server transmission rate is 10 times the peer upload rate, and (for simplicity) the peer download rates are set large enough so as not to have an effect. We see from Figure 2.23 that for the client-server architecture, the distribution time increases linearly and without bound as the number of peers increases. However, for the P2P architecture, the minimal distribution time is not only always less than the distribution time of the client-server architecture; it is also less than one hour for any number of peers N. Thus, applications with the P2P architecture can be self-scaling. This scalability is a direct consequence of peers being redistributors as well as consumers of bits.

Figure 2.23 Distribution time for P2P and client-server architectures

BitTorrent#

BitTorrent 是一个流行的 P2P 文件分发协议 [Chao 2011]。在 BitTorrent 术语中,参与特定文件分发的所有对等方集合称为一个 torrent。torrent 中的对等方彼此下载等大小的数据块,典型块大小为 256 KB。当对等方首次加入 torrent 时,尚未拥有任何块。随着时间推移,它会逐步积累更多块。在下载块的同时,它也将块上传给其他对等方。一旦获取完整文件,对等方可能(自私地)退出 torrent,也可能(无私地)留下继续为其他对等方上传块。此外,任一对等方可随时仅携部分块离开,并在之后重新加入 torrent。

下面我们详细介绍 BitTorrent 的运行方式。由于 BitTorrent 是一个相当复杂的协议与系统,我们将仅描述其最重要的机制,并略去一些细节;这样可以让我们把握整体概貌。每个 torrent 都有一个基础设施节点,称为 tracker。

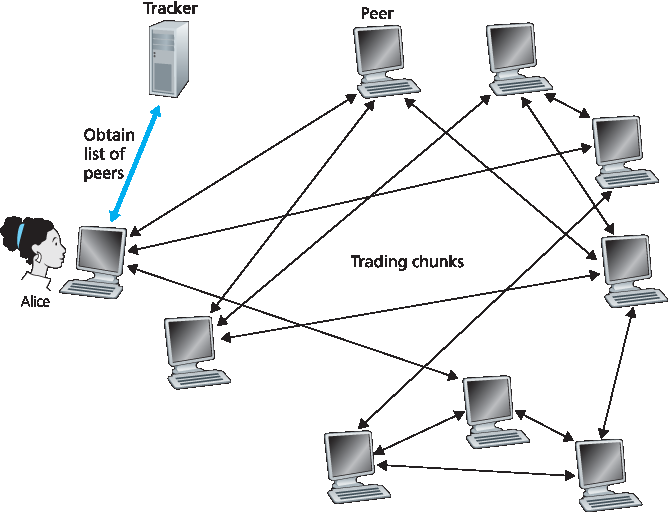

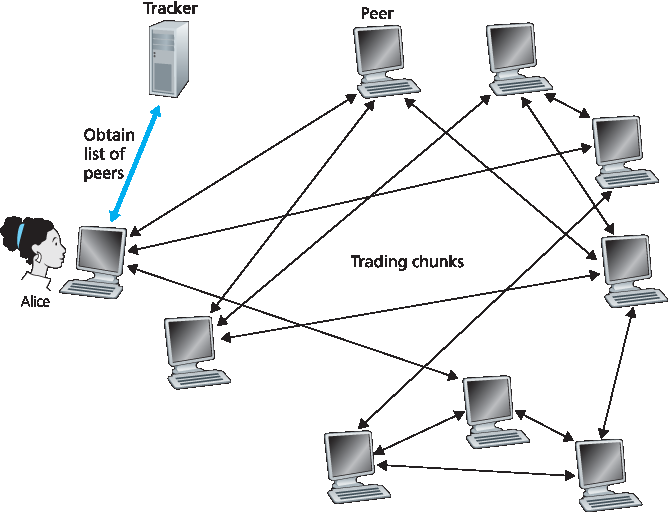

图 2.24 使用 BitTorrent 进行文件分发

当对等方加入 torrent 时,会向 tracker 注册,并定期通知其仍然在线。通过这种方式,tracker 记录当前参与 torrent 的对等方。某个 torrent 在任意时刻可能有少于 10 个或多达数千个对等方。

如 图 2.24 所示,当新对等方 Alice 加入 torrent 后,tracker 从参与对等方中随机选出一组(例如 50 个)并将其 IP 地址发送给 Alice。获得该列表后,Alice 会尝试同时与这些对等方建立 TCP 连接。我们称与 Alice 成功建立 TCP 连接的这些对等方为“邻居对等方”。(在 图 2.24 中,Alice 仅有 3 个邻居对等方,实际上可能更多。)随着时间推移,部分对等方可能离开,其他对等方(不在初始 50 个中)可能尝试与 Alice 建立连接。因此,某对等方的邻居会随时间变化。

任意时刻,每个对等方仅拥有部分数据块,且各对等方拥有的块集合不同。Alice 会周期性地向其邻居请求块列表(通过 TCP 连接)。如果 Alice 有 L 个邻居,则会获得 L 个块列表。Alice 据此向邻居请求自己尚未拥有的块。

任意时刻,Alice 拥有部分块,并知道其邻居各自拥有哪些块。基于此信息,Alice 面临两个关键决策:第一,从邻居处优先请求哪些块?第二,向哪些邻居发送请求的块?在决定请求哪些块时,Alice 使用一种称为 稀有优先 (rarest first)的方法。该方法旨在从尚未拥有的块中识别邻居中最稀有(副本最少)的块,并优先请求这些块。这样可以尽快扩散稀有块,趋于(大致)在整个 torrent 中平衡各块副本数量。

在决定响应哪些请求时,BitTorrent 使用一种巧妙的交易算法。基本思想是:Alice 优先响应当前上传速率最高的邻居。具体而言,Alice 持续测量每个邻居的上传速率,并选出上传速率最高的 4 个对等方。这 4 个对等方将获得 Alice 的块回传。每隔 10 秒,Alice 重新计算速率并更新这 4 个邻居。在 BitTorrent 术语中,这些对等方称为 unchoked。此外,每隔 30 秒,Alice 会随机选出另一个邻居(例如 Bob)并向其发送块。Bob 被称为 optimistically unchoked。由于 Alice 向 Bob 发送数据,Alice 可能成为 Bob 的上传速率前 4 名之一,进而 Bob 会开始向 Alice 发送数据。若 Bob 的上传速率足够高,他也可能成为 Alice 的前 4 上传者。也就是说,Alice 每 30 秒会随机选取一个交易对象并开始交易。若彼此满意,将互列为“前 4 名”,并持续交易,直至其中一方找到更优对象。这样上传能力匹配的对等方更容易彼此发现。随机选择机制也使新对等方获得块以供交换。除这 5 个(4 个 top + 1 个探索者)外的其他邻居将被 choked,即不接收 Alice 的任何块。BitTorrent 还有许多机制未在此详述,如片段(pieces)、流水线(pipelining)、随机优先选择、结束模式(endgame mode)以及防冷落(anti-snubbing) [Cohen 2003]。

上述交易激励机制常被称为 tit-for-tat [Cohen 2003]。虽然有研究指出该激励机制可被绕过 [ Liogkas 2006; Locher 2006;Piatek 2007],BitTorrent 生态依然极为成功,数百万对等方在成千上万个 torrent 中活跃共享。如果 BitTorrent 没有采用 tit-for-tat 或其变体,即使其它机制完全相同,BitTorrent 可能根本不会存活,因为大多数用户会成为搭便车者 [Saroiu 2002]。

在本节结尾,我们简要提及 P2P 的另一应用:分布式哈希表(DHT)。分布式哈希表是一个简单数据库,其记录分布在 P2P 系统的对等方中。DHT 被广泛实现(例如 BitTorrent 中),并成为重要研究主题。其概览见配套网站中的视频说明。

漫步分布式哈希表

BitTorrent is a popular P2P protocol for file distribution [Chao 2011] . In BitTorrent lingo, the collection of all peers participating in the distribution of a particular file is called a torrent. Peers in a torrent download equal-size chunks of the file from one another, with a typical chunk size of 256 KBytes. When a peer first joins a torrent, it has no chunks. Over time it accumulates more and more chunks. While it downloads chunks it also uploads chunks to other peers. Once a peer has acquired the entire file, it may (selfishly) leave the torrent, or (altruistically) remain in the torrent and continue to upload chunks to other peers. Also, any peer may leave the torrent at any time with only a subset of chunks, and later rejoin the torrent.

Let’s now take a closer look at how BitTorrent operates. Since BitTorrent is a rather complicated protocol and system, we’ll only describe its most important mechanisms, sweeping some of the details under the rug; this will allow us to see the forest through the trees. Each torrent has an infrastructure node called a tracker.

Figure 2.24 File distribution with BitTorrent

When a peer joins a torrent, it registers itself with the tracker and periodically informs the tracker that it is still in the torrent. In this manner, the tracker keeps track of the peers that are participating in the torrent. A given torrent may have fewer than ten or more than a thousand peers participating at any instant of time.

As shown in Figure 2.24, when a new peer, Alice, joins the torrent, the tracker randomly selects a subset of peers (for concreteness, say 50) from the set of participating peers, and sends the IP addresses of these 50 peers to Alice. Possessing this list of peers, Alice attempts to establish concurrent TCP connections with all the peers on this list. Let’s call all the peers with which Alice succeeds in establishing a TCP connection “neighboring peers.” (In Figure 2.24 , Alice is shown to have only three neighboring peers. Normally, she would have many more.) As time evolves, some of these peers may leave and other peers (outside the initial 50) may attempt to establish TCP connections with Alice. So a peer’s neighboring peers will fluctuate over time.

At any given time, each peer will have a subset of chunks from the file, with different peers having different subsets. Periodically, Alice will ask each of her neighboring peers (over the TCP connections) for the list of the chunks they have. If Alice has L different neighbors, she will obtain L lists of chunks. With this knowledge, Alice will issue requests (again over the TCP connections) for chunks she currently does not have.

So at any given instant of time, Alice will have a subset of chunks and will know which chunks her neighbors have. With this information, Alice will have two important decisions to make. First, which chunks should she request first from her neighbors? And second, to which of her neighbors should she send requested chunks? In deciding which chunks to request, Alice uses a technique called rarest first. The idea is to determine, from among the chunks she does not have, the chunks that are the rarest among her neighbors (that is, the chunks that have the fewest repeated copies among her neighbors) and then request those rarest chunks first. In this manner, the rarest chunks get more quickly redistributed, aiming to (roughly) equalize the numbers of copies of each chunk in the torrent.

To determine which requests she responds to, BitTorrent uses a clever trading algorithm. The basic idea is that Alice gives priority to the neighbors that are currently supplying her data at the highest rate. Specifically, for each of her neighbors, Alice continually measures the rate at which she receives bits and determines the four peers that are feeding her bits at the highest rate. She then reciprocates by sending chunks to these same four peers. Every 10 seconds, she recalculates the rates and possibly modifies the set of four peers. In BitTorrent lingo, these four peers are said to be unchoked. Importantly, every 30 seconds, she also picks one additional neighbor at random and sends it chunks. Let’s call the randomly chosen peer Bob. In BitTorrent lingo, Bob is said to be optimistically unchoked. Because Alice is sending data to Bob, she may become one of Bob’s top four uploaders, in which case Bob would start to send data to Alice. If the rate at which Bob sends data to Alice is high enough, Bob could then, in turn, become one of Alice’s top four uploaders. In other words, every 30 seconds, Alice will randomly choose a new trading partner and initiate trading with that partner. If the two peers are satisfied with the trading, they will put each other in their top four lists and continue trading with each other until one of the peers finds a better partner. The effect is that peers capable of uploading at compatible rates tend to find each other. The random neighbor selection also allows new peers to get chunks, so that they can have something to trade. All other neighboring peers besides these five peers (four “top” peers and one probing peer) are “choked,” that is, they do not receive any chunks from Alice. BitTorrent has a number of interesting mechanisms that are not discussed here, including pieces (mini- chunks), pipelining, random first selection, endgame mode, and anti-snubbing [Cohen 2003].

The incentive mechanism for trading just described is often referred to as tit-for-tat [Cohen 2003]. It has been shown that this incentive scheme can be circumvented [ Liogkas 2006; Locher 2006; Piatek 2007]. Nevertheless, the BitTorrent ecosystem is wildly successful, with millions of simultaneous peers actively sharing files in hundreds of thousands of torrents. If BitTorrent had been designed without tit-for-tat (or a variant), but otherwise exactly the same, BitTorrent would likely not even exist now, as the majority of the users would have been freeriders [Saroiu 2002].

We close our discussion on P2P by briefly mentioning another application of P2P, namely, Distributed Hast Table (DHT). A distributed hash table is a simple database, with the database records being distributed over the peers in a P2P system. DHTs have been widely implemented (e.g., in BitTorrent) and have been the subject of extensive research. An overview is provided in a Video Note in the companion website.

Walking though distributed hash tables