8.4 终端认证#

8.4 End-Point Authentication

终端认证 (End-point authentication)是指一个实体在计算机网络上向另一个实体证明自己身份的过程,例如,一个用户向电子邮件服务器证明其身份。作为人类,我们以多种方式相互认证:我们在见面时通过面孔相互识别,在电话中通过声音相互识别,海关官员通过核对护照上的照片来认证我们的身份。

在本节中,我们考虑两个通过网络通信的实体之间如何相互认证。我们重点关注在通信实际发生时,对“在线”一方进行认证的过程。一个具体的例子是用户向电子邮件服务器认证其身份。这与在 第8.3节 中研究的问题略有不同,后者关注的是如何证明某条消息确实来自所声称的发送者,即使消息是在过去某个时刻收到的。

在网络上执行身份认证时,通信双方无法依赖生物识别信息,例如外貌或声音特征。事实上,我们将在后续的案例研究中看到,往往是网络元素(如路由器和客户端/服务器进程)需要彼此认证。在这种情况下,认证只能基于 认证协议 中交换的消息和数据来完成。通常,认证协议在通信双方运行其他协议之前运行(例如可靠数据传输协议、路由信息交换协议或电子邮件协议)。认证协议首先建立双方对彼此身份的认可;只有在完成认证后,双方才开始后续的通信工作。

就像我们在 第3章 中开发可靠数据传输(rdt)协议那样,我们会发现,通过开发多个版本的认证协议(我们称之为 ap,即 authentication protocol)并逐步发现各个版本中的漏洞,是一种很有启发意义的方式。(如果你喜欢这种逐步演进的设计方式,或许你也会喜欢 [Bryant 1988],其中讲述了一群开放网络认证系统设计师之间的虚构对话,以及他们发现的各种微妙问题。)

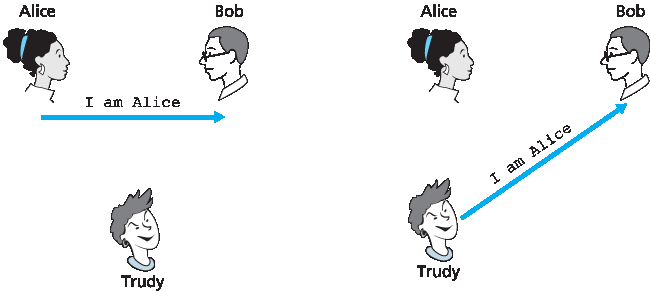

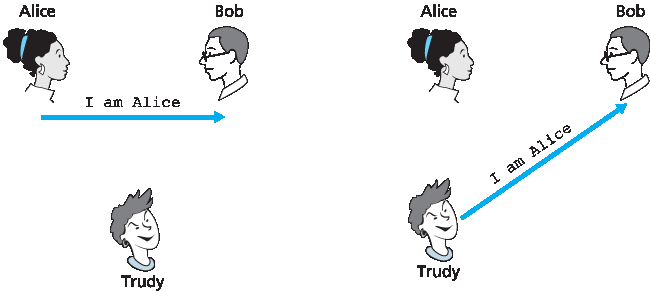

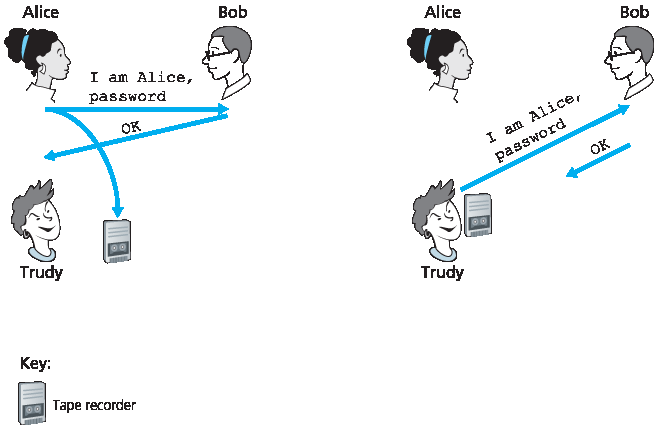

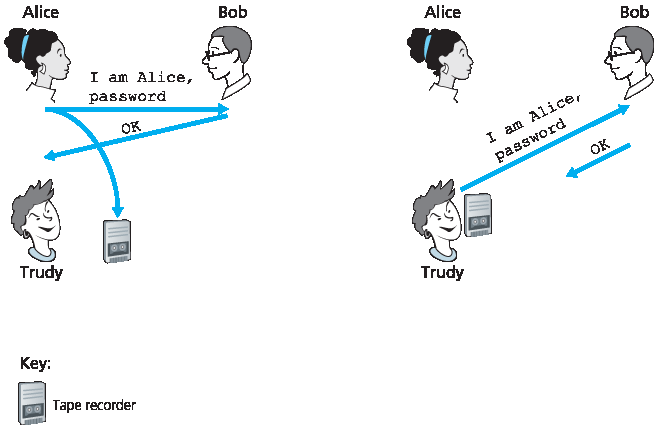

图 8.15 协议 ap1.0 及其失败场景

我们假设 Alice 需要向 Bob 认证她的身份。

End-point authentication is the process of one entity proving its identity to another entity over a computer network, for example, a user proving its identity to an e-mail server. As humans, we authenticate each other in many ways: We recognize each other’s faces when we meet, we recognize each other’s voices on the telephone, we are authenticated by the customs official who checks us against the picture on our passport.

In this section, we consider how one party can authenticate another party when the two are communicating over a network. We focus here on authenticating a “live” party, at the point in time when communication is actually occurring. A concrete example is a user authenticating him or herself to an e- mail server. This is a subtly different problem from proving that a message received at some point in the past did indeed come from that claimed sender, as studied in Section 8.3.

When performing authentication over the network, the communicating parties cannot rely on biometric information, such as a visual appearance or a voiceprint. Indeed, we will see in our later case studies that it is often network elements such as routers and client/server processes that must authenticate each other. Here, authentication must be done solely on the basis of messages and data exchanged as part of an authentication protocol. Typically, an authentication protocol would run before the two communicating parties run some other protocol (for example, a reliable data transfer protocol, a routing information exchange protocol, or an e-mail protocol). The authentication protocol first establishes the identities of the parties to each other’s satisfaction; only after authentication do the parties get down to the work at hand.

As in the case of our development of a reliable data transfer (rdt) protocol in Chapter 3, we will find it instructive here to develop various versions of an authentication protocol, which we will call ap (authentication protocol), and poke holes in each version as we proceed. (If you enjoy this stepwise evolution of a design, you might also enjoy [Bryant 1988], which recounts a fictitious narrative between designers of an open-network authentication system, and their discovery of the many subtle issues involved.)

Figure 8.15 Protocol ap1.0 and a failure scenario

Let’s assume that Alice needs to authenticate herself to Bob.

8.4.1 认证协议 ap1.0#

8.4.1 Authentication Protocol ap1.0

或许我们能想到的最简单的认证协议就是 Alice 仅仅向 Bob 发送一条消息,说她是 Alice。该协议如 图 8.15 所示。这个协议的漏洞是显而易见的——Bob 无法真正知道发送消息“我是 Alice”的人是否确实是 Alice。例如,Trudy(入侵者)同样可以发送这样一条消息。

Perhaps the simplest authentication protocol we can imagine is one where Alice simply sends a message to Bob saying she is Alice. This protocol is shown in Figure 8.15. The flaw here is obvious— there is no way for Bob actually to know that the person sending the message “I am Alice” is indeed Alice. For example, Trudy (the intruder) could just as well send such a message.

8.4.2 认证协议 ap2.0#

8.4.2 Authentication Protocol ap2.0

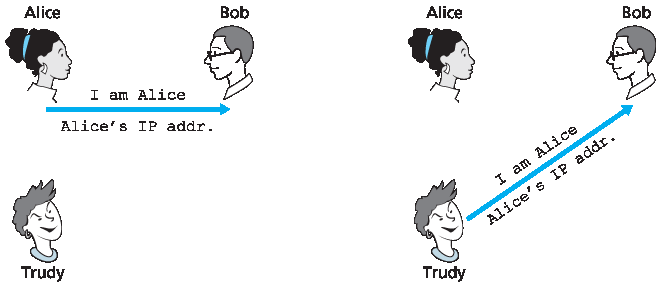

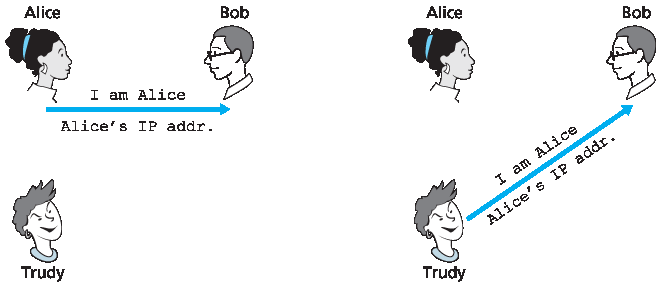

如果 Alice 有一个众所周知的网络地址(例如,一个固定的 IP 地址),她总是从这个地址进行通信,那么 Bob 可以尝试通过验证承载认证消息的 IP 数据报中的源地址是否与 Alice 的已知地址匹配来认证 Alice。在这种情况下,Alice 就被认证了。这或许能阻止一个对网络毫无概念的入侵者冒充 Alice,但它无法阻止在读这本书的学生,当然也无法阻止许多其他人!

根据我们对网络层和数据链路层的学习,我们知道要伪造一个 IP 数据报并不困难(例如,如果你能够访问操作系统代码并构建自己的操作系统内核——Linux 及其他几个开源操作系统就是如此),我们可以创建一个 IP 数据报,把我们想要的任何 IP 源地址(例如 Alice 的知名 IP 地址)写入该数据报中,然后通过链路层协议将其发送给首跳路由器。从那以后,这个源地址伪造的数据报就会被“忠实地”转发给 Bob。这种方法如 图 8.16 所示,是一种 IP 欺骗(IP spoofing)行为。如果 Trudy 的首跳路由器被配置为只转发包含 Trudy 自己 IP 源地址的数据报,则可以避免 IP 欺骗 [RFC 2827]。然而,这项功能并未被广泛部署或强制执行。因此,如果 Bob 轻信 Trudy 的网络管理员(或许就是 Trudy 本人)已经将 Trudy 的首跳路由器配置为只转发地址正确的数据报,那就太天真了。

图 8.16 协议 ap2.0 及其失败场景

If Alice has a well-known network address (e.g., an IP address) from which she always communicates, Bob could attempt to authenticate Alice by verifying that the source address on the IP datagram carrying the authentication message matches Alice’s well-known address. In this case, Alice would be authenticated. This might stop a very network-naive intruder from impersonating Alice, but it wouldn’t stop the determined student studying this book, or many others!

From our study of the network and data link layers, we know that it is not that hard (for example, if one had access to the operating system code and could build one’s own operating system kernel, as is the case with Linux and several other freely available operating systems) to create an IP datagram, put whatever IP source address we want (for example, Alice’s well-known IP address) into the IP datagram, and send the datagram over the link-layer protocol to the first-hop router. From then on, the incorrectly source-addressed datagram would be dutifully forwarded to Bob. This approach, shown in Figure 8.16, is a form of IP spoofing. IP spoofing can be avoided if Trudy’s first-hop router is configured to forward only datagrams containing Trudy’s IP source address [RFC 2827]. However, this capability is not universally deployed or enforced. Bob would thus be foolish to assume that Trudy’s network manager (who might be Trudy herself) had configured Trudy’s first-hop router to forward only appropriately addressed datagrams.

Figure 8.16 Protocol ap2.0 and a failure scenario

8.4.3 认证协议 ap3.0#

8.4.3 Authentication Protocol ap3.0

一种经典的认证方法是使用秘密密码。密码是在认证者和被认证者之间共享的机密。Gmail、Facebook、telnet、FTP 以及许多其他服务都使用密码认证。在协议 ap3.0 中,如 图 8.17 所示,Alice 向 Bob 发送她的秘密密码。

由于密码被广泛使用,我们可能会认为协议 ap3.0 是相当安全的。如果真这么认为,那我们就错了!其安全漏洞显而易见:如果 Trudy 窃听了 Alice 的通信,那么她就能获取 Alice 的密码。如果你认为这种情况不太可能发生,请考虑这样一个事实:当你使用 Telnet 登录到另一台机器时,登录密码是以明文形式发送给 Telnet 服务器的。任何连接到 Telnet 客户端或服务器所在 LAN 的人,都有可能嗅探(读取并存储)该局域网上传输的所有数据包,从而窃取登录密码。事实上,这是一种众所周知的窃取密码的方法(参见 [Jimenez 1997])。因此,这种威胁显然是真实存在的,ap3.0 显然行不通。

One classic approach to authentication is to use a secret password. The password is a shared secret between the authenticator and the person being authenticated. Gmail, Facebook, telnet, FTP, and many other services use password authentication. In protocol ap3.0, Alice thus sends her secret password to Bob, as shown in Figure 8.17.

Since passwords are so widely used, we might suspect that protocol ap3.0 is fairly secure. If so, we’d be wrong! The security flaw here is clear. If Trudy eavesdrops on Alice’s communication, then she can learn Alice’s password. Lest you think this is unlikely, consider the fact that when you Telnet to another machine and log in, the login password is sent unencrypted to the Telnet server. Someone connected to the Telnet client or server’s LAN can possibly sniff (read and store) all packets transmitted on the LAN and thus steal the login password. In fact, this is a well-known approach for stealing passwords (see, for example, [Jimenez 1997]). Such a threat is obviously very real, so ap3.0 clearly won’t do.

8.4.4 认证协议 ap3.1#

8.4.4 Authentication Protocol ap3.1

我们用来修复 ap3.0 的下一个想法,自然是对密码进行加密。通过加密密码,我们可以防止 Trudy 获取 Alice 的密码。如果我们假设 Alice 和 Bob 共享一个对称密钥 KA-B,那么 Alice 可以加密密码,并将她的身份信息 “我是 Alice” 以及加密后的密码发送给 Bob。Bob 随后解密密码,并在密码正确的前提下对 Alice 进行认证。Bob 感到可以信任 Alice 的身份,因为 Alice 不仅知道密码,而且还知道加密密码所需的共享密钥。我们将此协议称为 ap3.1。

图 8.17 协议 ap3.0 及其失败场景

虽然 ap3.1 确实可以防止 Trudy 获取 Alice 的密码,但此处使用加密技术并没有真正解决认证问题。Bob 仍然容易受到 重放攻击:Trudy 只需窃听 Alice 的通信,记录下加密版本的密码,然后将该加密密码重放给 Bob,假冒 Alice 的身份。协议 ap3.1 中使用加密密码的情况,并没有使其与 图 8.17 中的协议 ap3.0 本质上有所不同。

Our next idea for fixing ap3.0 is naturally to encrypt the password. By encrypting the password, we can prevent Trudy from learning Alice’s password. If we assume that Alice and Bob share a symmetric secret key, KA-B, then Alice can encrypt the password and send her identification message, “I am Alice,” and her encrypted password to Bob. Bob then decrypts the password and, assuming the password is correct, authenticates Alice. Bob feels comfortable in authenticating Alice since Alice not only knows the password, but also knows the shared secret key value needed to encrypt the password. Let’s call this protocol ap3.1.

Figure 8.17 Protocol ap3.0 and a failure scenario

While it is true that ap3.1 prevents Trudy from learning Alice’s password, the use of cryptography here does not solve the authentication problem. Bob is subject to a playback attack: Trudy need only eavesdrop on Alice’s communication, record the encrypted version of the password, and play back the encrypted version of the password to Bob to pretend that she is Alice. The use of an encrypted password in ap3.1 doesn’t make the situation manifestly different from that of protocol ap3.0 in Figure 8.17.

8.4.5 认证协议 ap4.0#

8.4.5 Authentication Protocol ap4.0

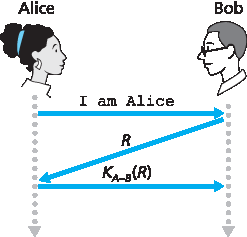

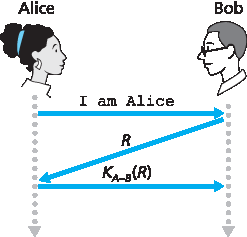

图 8.17 中的失败场景是因为 Bob 无法区分 Alice 的原始认证和之后的 Alice 原始认证的重放。也就是说,Bob 无法判断 Alice 是否是真实在线(即当前确实在连接的另一端),还是他收到的消息只是 Alice 先前认证的录音重放。非常(非常)细心的读者会记得,TCP 三次握手协议也需要解决同样的问题——TCP 连接的服务器端不希望接受一个连接请求,如果收到的 SYN 报文是早期连接中 SYN 报文的旧副本(重传)。TCP 服务器端是如何解决客户端是否真实在线的问题的呢?它选择一个很长时间未使用的初始序列号,将该序列号发送给客户端,然后等待客户端回复一个包含该序列号的 ACK 报文。我们也可以在这里采用相同的思路来进行认证。

Nonce 是协议中只使用一次的数字。也就是说,一旦协议使用了某个 nonce,就永远不会再次使用该数字。我们的 ap4.0 协议使用 nonce 的步骤如下:

Alice 发送消息 “我是 Alice” 给 Bob。

Bob 选择一个 nonce,R,并发送给 Alice。

Alice 使用 Alice 和 Bob 共享的对称密钥 KA-B 对 nonce 加密,然后将加密后的 nonce,KA-B (R),发送回 Bob。和协议 ap3.1 类似,Alice 知道并使用了 KA-B 来加密某个值,这让 Bob 知道他收到的消息确实是 Alice 生成的。nonce 用来确保 Alice 是实时在线的。

Bob 解密收到的消息。如果解密得到的 nonce 等于他发送给 Alice 的 nonce,则认证通过。

协议 ap4.0 如 图 8.18 所示。通过使用一次性数字 R,并检查返回的值 KA-B (R),Bob 可以确定 Alice 不仅是她所说的人(因为她知道加密 R 所需的密钥值),而且是实时在线的(因为她加密了 Bob 刚刚生成的 nonce R)。

nonce 和对称密钥密码学的结合构成了 ap4.0 的基础。一个自然的问题是,是否可以用 nonce 和公钥密码学(而非对称密钥密码学)来解决认证问题。本章末尾的习题将探讨这个问题。

图 8.18 协议 ap4.0 及其失败场景

The failure scenario in Figure 8.17 resulted from the fact that Bob could not distinguish between the original authentication of Alice and the later playback of Alice’s original authentication. That is, Bob could not tell if Alice was live (that is, was currently really on the other end of the connection) or whether the messages he was receiving were a recorded playback of a previous authentication of Alice. The very (very) observant reader will recall that the three-way TCP handshake protocol needed to address the same problem—the server side of a TCP connection did not want to accept a connection if the received SYN segment was an old copy (retransmission) of a SYN segment from an earlier connection. How did the TCP server side solve the problem of determining whether the client was really live? It chose an initial sequence number that had not been used in a very long time, sent that number to the client, and then waited for the client to respond with an ACK segment containing that number. We can adopt the same idea here for authentication purposes.

A nonce is a number that a protocol will use only once in a lifetime. That is, once a protocol uses a nonce, it will never use that number again. Our ap4.0 protocol uses a nonce as follows:

Alice sends the message “I am Alice” to Bob.

Bob chooses a nonce, R, and sends it to Alice.

Alice encrypts the nonce using Alice and Bob’s symmetric secret key, KA-B, and sends the encrypted nonce, KA-B (R), back to Bob. As in protocol ap3.1, it is the fact that Alice knows KA-B and uses it to encrypt a value that lets Bob know that the message he receives was generated by Alice. The nonce is used to ensure that Alice is live.

Bob decrypts the received message. If the decrypted nonce equals the nonce he sent Alice, then Alice is authenticated.

Protocol ap4.0 is illustrated in Figure 8.18. By using the once-in-a-lifetime value, R, and then checking the returned value, KA-B (R), Bob can be sure that Alice is both who she says she is (since she knows the secret key value needed to encrypt R) and live (since she has encrypted the nonce, R, that Bob just created).

The use of a nonce and symmetric key cryptography forms the basis of ap4.0. A natural question is whether we can use a nonce and public key cryptography (rather than symmetric key cryptography) to solve the authentication problem. This issue is explored in the problems at the end of the chapter.

Figure 8.18 Protocol ap4.0 and a failure scenario