7.5 移动性管理:原理#

7.5 Mobility Management: Principles

在讨论了无线网络中通信链路的无线特性之后,现在我们将注意力转向这些无线链路所支持的移动性。从广义上讲,移动节点是指其接入网络的点随时间变化的节点。由于“移动性”一词在计算机和电话通信领域中已具有多重含义,我们不妨先从几个维度详细探讨移动性的含义。

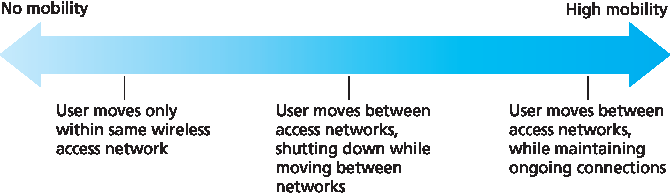

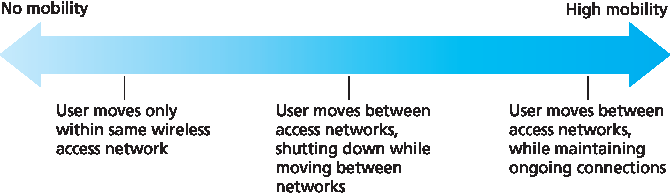

从网络层的角度看,用户的移动性有多强?一个在物理上处于移动状态的用户,其在网络层所带来的挑战会因其接入点的变化方式而大不相同。在 图7.22 的一端,用户可能带着一台装有无线网卡的笔记本电脑在建筑物中走动。正如我们在 第7.3.4节 中看到的,从网络层的角度来看,这个用户并不具备移动性。而且,如果该用户无论身处何地都连接到同一个接入点,那么从链路层角度来看,用户甚至也不具备移动性。

在光谱的另一端,设想用户驾驶着BMW或Tesla以150公里/小时的速度在高速公路上飞驰,在多个无线接入网络之间穿梭,并希望在整个行程中保持与远程应用的TCP连接不中断。这个用户显然是移动的!介于两者之间的是这样一位用户:他将笔记本电脑从一个地点(如办公室或宿舍)带到另一个地点(如咖啡馆或教室),并希望在新地点连接到网络。该用户同样具有移动性(尽管比驾驶BMW的用户要弱一些),但在移动过程中并不需要持续保持连接。图7.22 展示了从网络层角度观察的用户移动性的不同程度。

图7.22 从网络层视角看,不同程度的移动性

移动节点的地址始终保持不变有多重要?在移动电话系统中,当用户在不同运营商的移动电话网络之间移动时,其电话号码——本质上是该手机的网络层地址——始终保持不变。那么,当笔记本电脑在不同IP网络之间移动时,也必须保持相同的IP地址吗?

这个问题的答案在很大程度上取决于所运行的应用类型。对于那位希望在高速公路上以极高速度移动的同时保持与远程应用的TCP连接的BMW或Tesla车主来说,能够保持相同的IP地址将非常便利。回忆一下我们在 第3章 中提到的,互联网应用需要知道远程实体的IP地址和端口号。如果移动实体在移动过程中能保持其IP地址不变,那么从应用的角度看,移动性将是透明的。这种透明性非常有价值——应用无需考虑IP地址变化问题,且相同的应用代码可同时适用于移动和非移动连接。我们将在下一节中看到,移动IP正是提供这种透明性的机制,它允许移动节点在网络之间移动时保持其永久IP地址不变。

另一方面,一位较普通的移动用户也许只是想关闭办公室的笔记本电脑,将其带回家中,开机并从家里工作。如果这台笔记本电脑主要作为客户端使用(如发送/接收电子邮件、浏览网页、Telnet连接远程主机),那么它所使用的具体IP地址并不重要。实际上,只要有一个ISP在家中临时分配给该笔记本的地址就足够了。我们在 第4.3节 中已经看到,DHCP正好可以提供这种功能。

是否存在支持的有线基础设施 ?在上述所有场景中,我们默认假设存在某种固定基础设施供移动用户连接——例如家庭的ISP网络、办公室的无线接入网络,或高速公路沿线的无线接入网络。如果没有这样的基础设施怎么办?如果两个用户处于彼此通信的范围内,在没有任何其他网络层基础设施的情况下,他们能否建立网络连接?自组织网络(Ad hoc 网络)正是提供此类能力的一种方式。这个快速发展的领域是移动网络研究的前沿内容,超出了本书的讨论范围。[Perkins 2000] 以及IETF的移动自组织网络工作组(manet)网页 [manet 2016] 对该主题有详细介绍。

为了说明在用户在网络间移动时保持连接所涉及的问题,我们可以类比一个现实生活的情境。一个二十多岁的成年人搬离父母家后变得“移动”,住在一系列宿舍和/或公寓中,经常更换地址。如果一位老朋友想联系他/她,应该如何找到这位移动朋友的地址?一种常见方法是联系其家庭住址,因为这个移动成年人通常会向家人登记其当前住址(哪怕只是为了能让父母给他寄生活费!)。父母的家——一个固定不变的地址——就成了别人联系该移动成年人的第一站。朋友后续的通信可能是间接的(例如邮件先寄到父母家,再由父母转发给他),也可能是直接的(朋友从父母处获得地址后直接寄送邮件)。

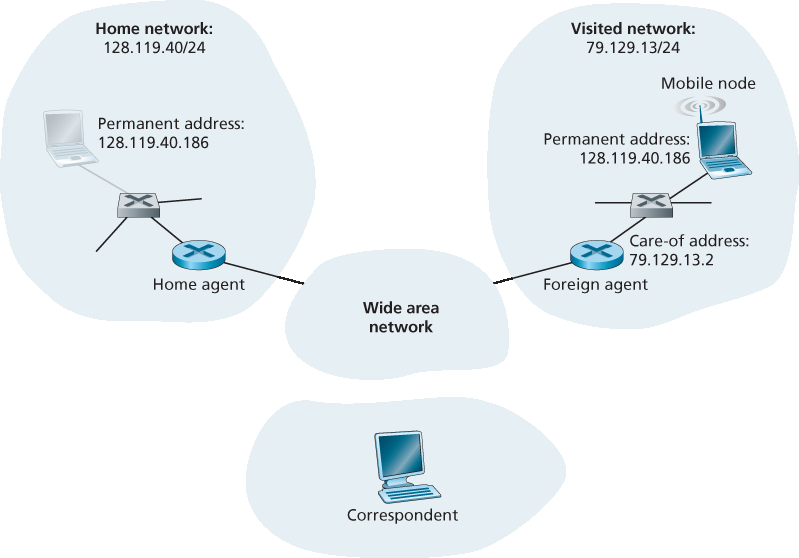

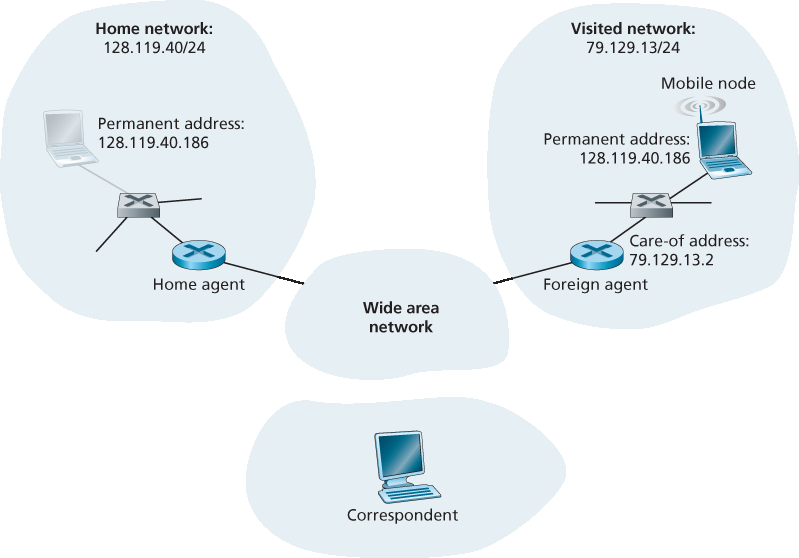

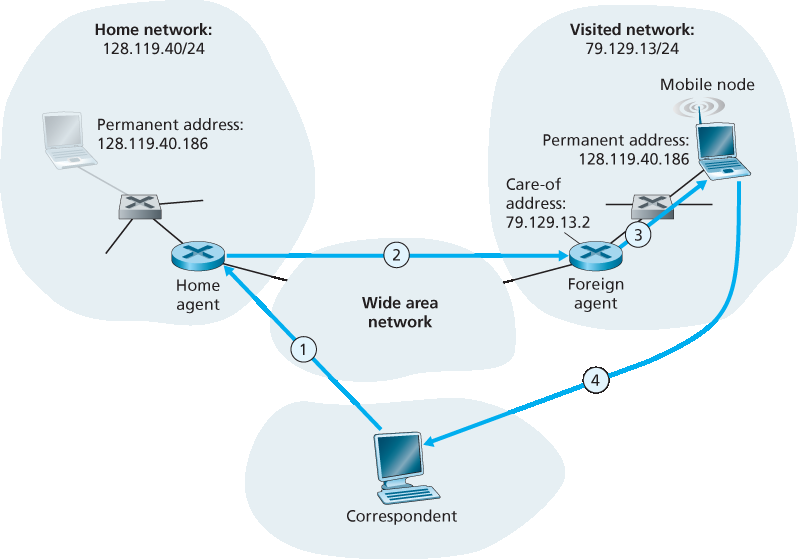

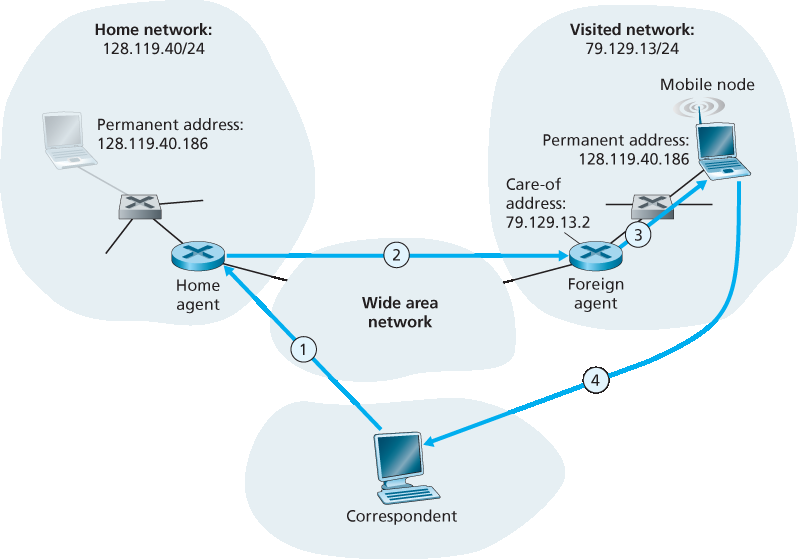

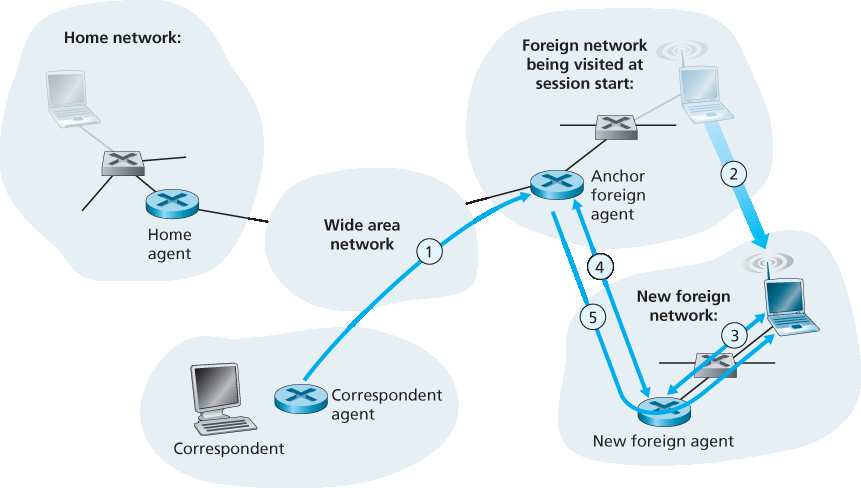

在网络场景中,移动节点(如笔记本电脑或智能手机)的永久所在网络称为 归属网络(home network),该网络中代表该移动节点执行移动性管理功能的实体称为 归属代理(home agent)。移动节点当前所在的网络称为 外部网络(foreign network) 或 访问网络(visited network),其中帮助移动节点执行移动性管理功能的实体称为 外部代理(foreign agent)。对于移动专业人员而言,他们的归属网络可能是其公司网络,而所访问的网络可能是他们正在拜访的同事的网络。 通信对应方(correspondent) 是指希望与移动节点进行通信的实体。图7.23 展示了这些概念,以及下文将讨论的寻址概念。在 图7.23 中,代理被示意为与路由器共置(例如作为运行在路由器上的进程),但它们也可以运行在网络中的其他主机或服务器上。

Having covered the wireless nature of the communication links in a wireless network, it’s now time to turn our attention to the mobility that these wireless links enable. In the broadest sense, a mobile node is one that changes its point of attachment into the network over time. Because the term mobility has taken on many meanings in both the computer and telephony worlds, it will serve us well first to consider several dimensions of mobility in some detail.

From the network layer’s standpoint, how mobile is a user? A physically mobile user will present a very different set of challenges to the network layer, depending on how he or she moves between points of attachment to the network. At one end of the spectrum in Figure 7.22, a user may carry a laptop with a wireless network interface card around in a building. As we saw in Section 7.3.4, this user is not mobile from a network-layer perspective. Moreover, if the user associates with the same access point regardless of location, the user is not even mobile from the perspective of the link layer.

At the other end of the spectrum, consider the user zooming along the autobahn in a BMW or Tesla at 150 kilometers per hour, passing through multiple wireless access networks and wanting to maintain an uninterrupted TCP connection to a remote application throughout the trip. This user is definitely mobile! In between these extremes is a user who takes a laptop from one location (e.g., office or dormitory) into another (e.g., coffeeshop, classroom) and wants to connect into the-network in the new location. This user is also mobile (although less so than the BMW driver!) but does not need to maintain an ongoing connection while moving between points of attachment to the network. Figure 7.22 illustrates this spectrum of user mobility from the network layer’s perspective.

Figure 7.22 Various degrees of mobility, from the network layer’s point of view

How important is it for the mobile node’s address to always remain the same? With mobile telephony, your phone number—essentially the network-layer address of your phone—remains the same as you travel from one provider’s mobile phone network to another. Must a laptop similarly maintain the same IP address while moving between IP networks?

The answer to this question will depend strongly on the applications being run. For the BMW or Tesla driver who wants to maintain an uninterrupted TCP connection to a remote application while zipping along the autobahn, it would be convenient to maintain the same IP address. Recall from Chapter 3 that an Internet application needs to know the IP address and port number of the remote entity with which it is communicating. If a mobile entity is able to maintain its IP address as it moves, mobility becomes invisible from the application standpoint. There is great value to this transparency —an application need not be concerned with a potentially changing IP address, and the same application code serves mobile and nonmobile connections alike. We’ll see in the following section that mobile IP provides this transparency, allowing a mobile node to maintain its permanent IP address while moving among networks.

On the other hand, a less glamorous mobile user might simply want to turn off an office laptop, bring that laptop home, power up, and work from home. If the laptop functions primarily as a client in client-server applications (e.g., send/read e-mail, browse the Web, Telnet to a remote host) from home, the particular IP address used by the laptop is not that important. In particular, one could get by fine with an address that is temporarily allocated to the laptop by the ISP serving the home. We saw in Section 4.3 that DHCP already provides this functionality.

What supporting wired infrastructure is available? In all of our scenarios above, we’ve implicitly assumed that there is a fixed infrastructure to which the mobile user can connect—for example, the home’s ISP network, the wireless access network in the office, or the wireless access networks lining the autobahn. What if no such infrastructure exists? If two users are within communication proximity of each other, can they establish a network connection in the absence of any other network-layer infrastructure? Ad hoc networking provides precisely these capabilities. This rapidly developing area is at the cutting edge of mobile networking research and is beyond the scope of this book. [Perkins 2000] and the IETF Mobile Ad Hoc Network (manet) working group Web pages [manet 2016] provide thorough treatments of the subject.

In order to illustrate the issues involved in allowing a mobile user to maintain ongoing connections while moving between networks, let’s consider a human analogy. A twenty-something adult moving out of the family home becomes mobile, living in a series of dormitories and/or apartments, and often changing addresses. If an old friend wants to get in touch, how can that friend find the address of her mobile friend? One common way is to contact the family, since a mobile adult will often register his or her current address with the family (if for no other reason than so that the parents can send money to help pay the rent!). The family home, with its permanent address, becomes that one place that others can go as a first step in communicating with the mobile adult. Later communication from the friend may be either indirect (for example, with mail being sent first to the parents’ home and then forwarded to the mobile adult) or direct (for example, with the friend using the address obtained from the parents to send mail directly to her mobile friend).

In a network setting, the permanent home of a mobile node (such as a laptop or smartphone) is known as the home network, and the entity within the home network that performs the mobility management functions discussed below on behalf of the mobile node is known as the home agent. The network in which the mobile node is currently residing is known as the foreign (or visited) network, and the entity within the foreign network that helps the mobile node with the mobility management functions discussed below is known as a foreign agent. For mobile professionals, their home network might likely be their company network, while the visited network might be the network of a colleague they are visiting. A correspondent is the entity wishing to communicate with the mobile node. Figure 7.23 illustrates these concepts, as well as addressing concepts considered below. In Figure 7.23, note that agents are shown as being collocated with routers (e.g., as processes running on routers), but alternatively they could be executing on other hosts or servers in the network.

7.5.1 地址分配#

7.5.1 Addressing

我们在上文中指出,为了使用户的移动性对网络应用保持透明,理想情况下,移动节点在从一个网络移动到另一个网络时应保持其地址不变。当移动节点驻留在外部网络中时,所有发送至该节点永久地址的通信流量现在都需要被路由到外部网络。那么该如何实现呢?一种选择是让外部网络向所有其他网络通告该移动节点目前驻留在其网络中。这可以通过通常的域内和域间路由信息交换实现,并且只需要对现有路由基础设施做很少的更改。外部网络只需向其邻居通告其拥有一条指向移动节点永久地址的高度特定的路由(也就是说,本质上告诉其他网络它拥有将数据报正确路由到该永久地址的路径;参见 第4.3节)。这些邻居随后会在更新路由信息和转发表的常规过程中将此路由信息传播到整个网络中。当移动节点离开一个外部网络并加入另一个网络时,新加入的外部网络将通告一条新的高度特定的路由,而原来的外部网络则撤回其关于该移动节点的路由信息。

图7.23 移动网络架构的初始元素

这种方法同时解决了两个问题,而且无需对网络层基础设施进行重大更改。其他网络可以获知移动节点的位置,并且路由数据报到该移动节点变得容易,因为转发表会将数据报定向到该外部网络。然而,这种方法的一个重大缺点是可扩展性问题。如果将移动性管理交由网络路由器负责,那么这些路由器就必须维护数百万个移动节点的转发表项,并在节点移动时更新这些表项。本章末尾的问题部分还探讨了该方法的一些其他缺陷。

另一种替代方案(也是实际中被采纳的方法)是将移动性功能从网络核心推向网络边缘——这是我们研究互联网架构时反复出现的主题。通过移动节点的归属网络来实现这一点是非常自然的方式。就像移动青年的父母追踪孩子的位置一样,移动节点的归属网络中的归属代理可以追踪移动节点当前所驻留的外部网络。移动节点(或代表其的外部代理)与归属代理之间一定需要某种协议来更新该移动节点的位置。

现在让我们更详细地考察外部代理。在概念上最简单的方法(见 图7.23)是将外部代理部署在外部网络的边缘路由器上。外部代理的一个作用是为移动节点创建一个所谓的 关联系地址(COA, care-of address),其中COA的网络部分与外部网络匹配。因此,移动节点拥有两个地址,一个是其 永久地址 (类似于我们所说的移动青年家庭住址),另一个是COA,有时也称为外部地址(类似于移动青年目前所住的房屋地址)。在 图7.23 的示例中,移动节点的永久地址是128.119.40.186。当其访问网络79.129.13/24时,其COA为79.129.13.2。外部代理的第二个作用是通知归属代理:该移动节点目前驻留在它(即该外部代理)的网络中,并且拥有该COA。我们很快就会看到,COA将用于通过外部代理将数据报“重新路由”至移动节点。

尽管我们在功能上区分了移动节点和外部代理,但值得注意的是,移动节点本身也可以承担外部代理的职责。例如,移动节点可以在外部网络中获取一个COA(例如,使用DHCP等协议),并自己将该COA通知归属代理。

We noted above that in order for user mobility to be transparent to network applications, it is desirable for a mobile node to keep its address as it moves from one network to another. When a mobile node is resident in a foreign network, all traffic addressed to the node’s permanent address now needs to be routed to the foreign network. How can this be done? One option is for the foreign network to advertise to all other networks that the mobile node is resident in its network. This could be via the usual exchange of intradomain and interdomain routing information and would require few changes to the existing routing infrastructure. The foreign network could simply advertise to its neighbors that it has a highly specific route to the mobile node’s permanent address (that is, essentially inform other networks that it has the correct path for routing datagrams to the mobile node’s permanent address; see Section 4.3). These neighbors would then propagate this routing information throughout the network as part of the normal procedure of updating routing information and forwarding tables. When the mobile node leaves one foreign network and joins another, the new foreign network would advertise a new, highly specific route to the mobile node, and the old foreign network would withdraw its routing information regarding the mobile node.

Figure 7.23 Initial elements of a mobile network architecture

This solves two problems at once, and it does so without making significant changes to the network- layer infrastructure. Other networks know the location of the mobile node, and it is easy to route datagrams to the mobile node, since the forwarding tables will direct datagrams to the foreign network. A significant drawback, however, is that of scalability. If mobility management were to be the responsibility of network routers, the routers would have to maintain forwarding table entries for potentially millions of mobile nodes, and update these entries as nodes move. Some additional drawbacks are explored in the problems at the end of this chapter.

An alternative approach (and one that has been adopted in practice) is to push mobility functionality from the network core to the network edge—a recurring theme in our study of Internet architecture. A natural way to do this is via the mobile node’s home network. In much the same way that parents of the mobile twenty-something track their child’s location, the home agent in the mobile node’s home network can track the foreign network in which the mobile node resides. A protocol between the mobile node (or a foreign agent representing the mobile node) and the home agent will certainly be needed to update the mobile node’s location.

Let’s now consider the foreign agent in more detail. The conceptually simplest approach, shown in Figure 7.23, is to locate foreign agents at the edge routers in the foreign network. One role of the foreign agent is to create a so-called care-of address (COA) for the mobile node, with the network portion of the COA matching that of the foreign network. There are thus two addresses associated with a mobile node, its permanent address (analogous to our mobile youth’s family’s home address) and its COA, sometimes known as a foreign address (analogous to the address of the house in which our mobile youth is currently residing). In the example in Figure 7.23, the permanent address of the mobile node is 128.119.40.186. When visiting network 79.129.13/24, the mobile node has a COA of 79.129.13.2. A second role of the foreign agent is to inform the home agent that the mobile node is resident in its (the foreign agent’s) network and has the given COA. We’ll see shortly that the COA will be used to “reroute” datagrams to the mobile node via its foreign agent.

Although we have separated the functionality of the mobile node and the foreign agent, it is worth noting that the mobile node can also assume the responsibilities of the foreign agent. For example, the mobile node could obtain a COA in the foreign network (for example, using a protocol such as DHCP) and itself inform the home agent of its COA.

7.5.2 移动节点的路由#

7.5.2 Routing to a Mobile Node

我们已经了解了移动节点如何获取COA,以及归属代理如何被告知该地址。但让归属代理知道COA只解决了部分问题。应如何对数据报进行寻址和转发以到达移动节点?由于只有归属代理(而不是网络范围内的路由器)知道移动节点的位置,因此仅仅将数据报发送到移动节点的永久地址并注入网络层基础设施已经不再足够。必须采取进一步的措施。可以识别出两种方法,我们称之为间接路由和直接路由。

We have now seen how a mobile node obtains a COA and how the home agent can be informed of that address. But having the home agent know the COA solves only part of the problem. How should datagrams be addressed and forwarded to the mobile node? Since only the home agent (and not network-wide routers) knows the location of the mobile node, it will no longer suffice to simply address a datagram to the mobile node’s permanent address and send it into the network-layer infrastructure. Something more must be done. Two approaches can be identified, which we will refer to as indirect and direct routing.

间接路由到移动节点#

Indirect Routing to a Mobile Node

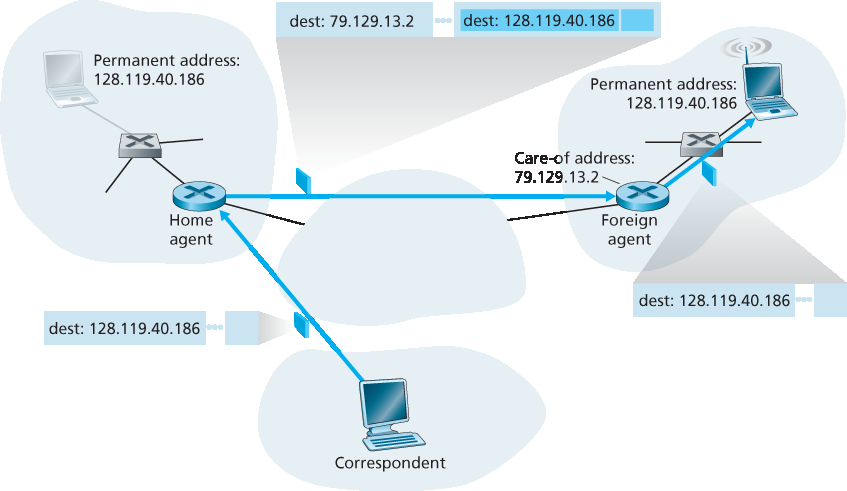

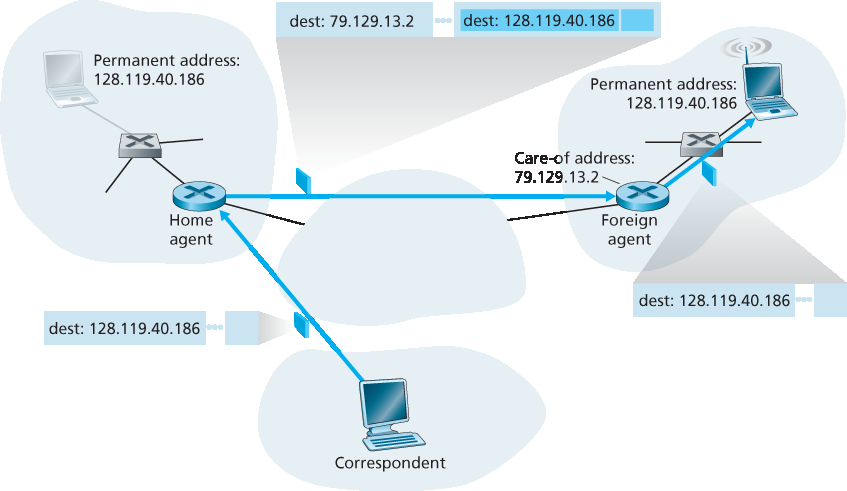

我们首先考虑一个希望向移动节点发送数据报的通信对应方。在 间接路由 方法中,对应方仅将数据报地址设为移动节点的永久地址,并将该数据报发送到网络中,而不必知晓移动节点是否驻留在其归属网络中或访问的是外部网络;因此,对应方对移动性的感知是完全透明的。这样的数据报首先按照通常方式被路由到移动节点的归属网络。如 图7.24 中的步骤1所示。

接下来我们关注归属代理。除了负责与外部代理交互以跟踪移动节点的COA之外,归属代理还有一个非常重要的功能。它的第二个任务是监视那些目标地址属于归属代理所属网络、但目前实际驻留在外部网络中的节点的数据报。归属代理截获这些数据报,并以两步方式将它们转发给移动节点。首先,数据报被使用移动节点的COA转发至外部代理(图7.24 中的步骤2),然后由外部代理再转发至移动节点(步骤3)。

图7.24 向移动节点的间接路由

进一步详细分析该重路由过程很有启发性。归属代理需要使用移动节点的COA对数据报进行寻址,以便网络层能将数据报路由到外部网络。另一方面,希望保持对应方的数据报不变,因为接收该数据报的应用不应察觉数据报曾经被经由归属代理转发。这两个目标可以通过让归属代理将对应方的原始完整数据报 封装 在一个新的(更大的)数据报中来实现。这个更大的数据报使用COA进行寻址和传输。拥有该COA的外部代理接收并对数据报进行解封装,即从封装的数据报中移除原始数据报并将其转发给移动节点(图7.24 的步骤3)。图7.25 显示了一个对应方的原始数据报如何被发送到归属网络,封装后发送到外部代理,以及最终原始数据报被传递给移动节点的过程。细心的读者会注意到,这里的封装/解封装与 第4.3节 中在IP组播与IPv6上下文中讨论的隧道技术完全一致。

接下来考虑移动节点如何向对应方发送数据报。这相对简单,移动节点可以直接将其数据报地址设为对应方地址(使用自己的永久地址作为源地址,对应方地址作为目的地址)。由于移动节点知道对应方地址,因此无需将数据报回送至归属代理。此过程在 图7.24 中作为步骤4展示。

图7.25 封装与解封装

我们通过列出支持移动性所需的新网络层功能,对间接路由的讨论做一个总结:

移动节点到外部代理协议。移动节点在连接到外部网络时向外部代理注册;离开外部网络时向其注销。

外部代理到归属代理注册协议。外部代理将移动节点的COA注册给归属代理。当移动节点离开该外部网络时,外部代理无需显式注销COA,因为移动节点注册新COA的后续操作会覆盖旧的。

归属代理的数据报封装协议。将对应方原始数据报封装在一个以COA为目的地址的新数据报中,并转发。

外部代理的解封装协议。从封装的数据报中提取原始数据报,并转发给移动节点。

上述讨论已提供所有构建块——外部代理、归属代理和间接转发——以使移动节点在跨网络移动的过程中维持连接。例如,假设移动节点连接至外部网络A,在该网络注册了一个COA,并通过其归属代理间接接收数据报。此时移动节点迁移到外部网络B,并在该网络中向新的外部代理注册,外部代理随后通知归属代理其新的COA。从此之后,归属代理将数据报重定向至外部网络B。对于通信对应方而言,移动性是透明的——数据报在移动前后始终通过相同的归属代理进行路由。对于归属代理而言,数据报的转发流程不受影响——原本是转发至网络A,COA更改后则转发至网络B。但移动节点是否会在跨网络移动期间遇到数据报中断?只要从断开网络A连接(此时无法再通过A接收数据报)到连接网络B(并向归属代理注册新COA)之间的时间足够短,那么丢失的数据报数量将很少。请回忆 第3章 的内容,端到端连接可能因网络拥塞而丢包。因此,在节点跨网络移动期间偶发的数据报丢失并不是灾难性的问题。如果需要无丢失通信,上层机制将负责数据报恢复,不论其丢失源于网络拥塞还是用户移动。

间接路由方法被用于移动IP标准中 [RFC 5944],将在 第7.6节 中进行讨论。

Let’s first consider a correspondent that wants to send a datagram to a mobile node. In the indirect routing approach, the correspondent simply addresses the datagram to the mobile node’s permanent address and sends the datagram into the network, blissfully unaware of whether the mobile node is resident in its home network or is visiting a foreign network; mobility is thus completely transparent to the correspondent. Such datagrams are first routed, as usual, to the mobile node’s home network. This is illustrated in step 1 in Figure 7.24.

Let’s now turn our attention to the home agent. In addition to being responsible for interacting with a foreign agent to track the mobile node’s COA, the home agent has another very important function. Its second job is to be on the lookout for arriving datagrams addressed to nodes whose home network is that of the home agent but that are currently resident in a foreign network. The home agent intercepts these datagrams and then forwards them to a mobile node in a two-step process. The datagram is first forwarded to the foreign agent, using the mobile node’s COA (step 2 in Figure 7.24), and then forwarded from the foreign agent to the mobile node (step 3 in Figure 7.24).

Figure 7.24 Indirect routing to a mobile node

It is instructive to consider this rerouting in more detail. The home agent will need to address the datagram using the mobile node’s COA, so that the network layer will route the datagram to the foreign network. On the other hand, it is desirable to leave the correspondent’s datagram intact, since the application receiving the datagram should be unaware that the datagram was forwarded via the home agent. Both goals can be satisfied by having the home agent encapsulate the correspondent’s original complete datagram within a new (larger) datagram. This larger datagram is addressed and delivered to the mobile node’s COA. The foreign agent, who “owns” the COA, will receive and decapsulate the datagram—that is, remove the correspondent’s original datagram from within the larger encapsulating datagram and forward (step 3 in Figure 7.24) the original datagram to the mobile node. Figure 7.25 shows a correspondent’s original datagram being sent to the home network, an encapsulated datagram being sent to the foreign agent, and the original datagram being delivered to the mobile node. The sharp reader will note that the encapsulation/decapsulation described here is identical to the notion of tunneling, discussed in Section 4.3 in the context of IP multicast and IPv6.

Let’s next consider how a mobile node sends datagrams to a correspondent. This is quite simple, as the mobile node can address its datagram directly to the correspondent (using its own permanent address as the source address, and the correspondent’s address as the destination address). Since the mobile node knows the correspondent’s address, there is no need to route the datagram back through the home agent. This is shown as step 4 in Figure 7.24.

Figure 7.25 Encapsulation and decapsulation

Let’s summarize our discussion of indirect routing by listing the new network-layer functionality required to support mobility.

A mobile-node–to–foreign-agent protocol. The mobile node will register with the foreign agent when attaching to the foreign network. Similarly, a mobile node will deregister with the foreign agent when it leaves the foreign network.

A foreign-agent–to–home-agent registration protocol. The foreign agent will register the mobile node’s COA with the home agent. A foreign agent need not explicitly deregister a COA when a

mobile node leaves its network, because the subsequent registration of a new COA, when the mobile node moves to a new network, will take care of this. - A home-agent datagram encapsulation protocol. Encapsulation and forwarding of the correspondent’s original datagram within a datagram addressed to the COA. - A foreign-agent decapsulation protocol. Extraction of the correspondent’s original datagram from the encapsulating datagram, and the forwarding of the original datagram to the mobile node.

The previous discussion provides all the pieces—foreign agents, the home agent, and indirect forwarding—needed for a mobile node to maintain an ongoing connection while moving among networks. As an example of how these pieces fit together, assume the mobile node is attached to foreign network A, has registered a COA in network A with its home agent, and is receiving datagrams that are being indirectly routed through its home agent. The mobile node now moves to foreign network B and registers with the foreign agent in network B, which informs the home agent of the mobile node’s new COA. From this point on, the home agent will reroute datagrams to foreign network B. As far as a correspondent is concerned, mobility is transparent—datagrams are routed via the same home agent both before and after the move. As far as the home agent is concerned, there is no disruption in the flow of datagrams—arriving datagrams are first forwarded to foreign network A; after the change in COA, datagrams are forwarded to foreign network B. But will the mobile node see an interrupted flow of datagrams as it moves between networks? As long as the time between the mobile node’s disconnection from network A (at which point it can no longer receive datagrams via A) and its attachment to network B (at which point it will register a new COA with its home agent) is small, few datagrams will be lost. Recall from Chapter 3 that end-to-end connections can suffer datagram loss due to network congestion. Hence occasional datagram loss within a connection when a node moves between networks is by no means a catastrophic problem. If loss-free communication is required, upper- layer mechanisms will recover from datagram loss, whether such loss results from network congestion or from user mobility.

An indirect routing approach is used in the mobile IP standard [RFC 5944], as discussed in Section 7.6.

直接路由到移动节点#

Direct Routing to a Mobile Node

图7.24 所示的间接路由方法存在一个被称为 三角路由问题 的效率问题——数据报必须先被路由到归属代理,再转发至外部网络,即使通信对应方与移动节点之间存在更高效的直接路径。在最糟糕的情况下,想象一个用户正在访问某位同事的外部网络,两人坐在一起通过网络交换数据。对应方(即该同事)发送的数据报被先转发至移动用户的归属代理,然后又返回同一个外部网络!

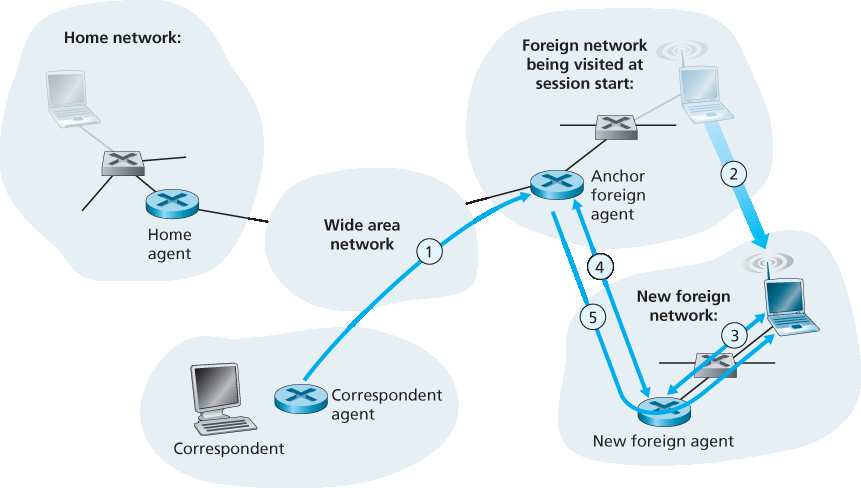

直接路由 克服了三角路由的低效问题,但也带来了额外的复杂性。在直接路由方法中,对应方所在网络中的一个 对应代理 首先需获知移动节点的COA。这可以通过查询归属代理实现,前提是(如同间接路由的情况)移动节点已在其归属代理注册了最新的COA。对应方本身也可以承担对应代理的职责,正如移动节点也可以承担外部代理的功能一样。如 图7.26 中的步骤1和2所示。对应代理随后直接将数据报通过隧道发送至移动节点的COA,方式类似于归属代理进行的隧道传输(见步骤3和4)。

图7.26 向移动用户的直接路由

尽管直接路由克服了三角路由问题,但它引入了两个重要的额外挑战:

一个移动用户位置协议,用于让对应代理查询归属代理以获取移动节点的COA(见 图7.26 中的步骤1和2)。

当移动节点从一个外部网络移动到另一个外部网络时,如何将数据报路由到新的外部网络?在间接路由方法中,这一问题通过更新归属代理保存的COA很容易解决。但在直接路由中,对应代理只在会话开始时向归属代理查询一次COA。因此,仅更新归属代理中的COA还不足以解决将数据报路由到新网络的问题。

一种解决方案是创建一个新协议,通知对应方COA的变更。另一种方案(我们将在GSM网络中看到此方案被采用)如下:假设数据当前被发送至最初启动会话时移动节点所在的外部网络(图7.27 的步骤1)。我们称该外部网络中的外部代理为 锚点外部代理 。当移动节点迁移至新的外部网络(步骤2)时,它会在新的外部代理处注册(步骤3),新的外部代理将新的COA提供给锚点外部代理(步骤4)。当锚点外部代理接收到原本发送给已离开节点的封装数据报时,它可以重新封装该数据报,并使用新的COA将其转发至移动节点(步骤5)。如果移动节点之后再次迁移至另一个新的外部网络,那么该新网络中的外部代理将联系锚点外部代理以建立新的转发路径。

图7.27 移动节点在直接路由下的网络间迁移

The indirect routing approach illustrated in Figure 7.24 suffers from an inefficiency known as the triangle routing problem—datagrams addressed to the mobile node must be routed first to the home agent and then to the foreign network, even when a much more efficient route exists between the correspondent and the mobile node. In the worst case, imagine a mobile user who is visiting the foreign network of a colleague. The two are sitting side by side and exchanging data over the network. Datagrams from the correspondent (in this case the colleague of the visitor) are routed to the mobile user’s home agent and then back again to the foreign network!

Direct routing overcomes the inefficiency of triangle routing, but does so at the cost of additional complexity. In the direct routing approach, a correspondent agent in the correspondent’s network first learns the COA of the mobile node. This can be done by having the correspondent agent query the home agent, assuming that (as in the case of indirect routing) the mobile node has an up-to-date value for its COA registered with its home agent. It is also possible for the correspondent itself to perform the function of the correspondent agent, just as a mobile node could perform the function of the foreign agent. This is shown as steps 1 and 2 in Figure 7.26. The correspondent agent then tunnels datagrams directly to the mobile node’s COA, in a manner analogous to the tunneling performed by the home agent, steps 3 and 4 in Figure 7.26.

While direct routing overcomes the triangle routing problem, it introduces two important additional challenges:

A mobile-user location protocol is needed for the correspondent agent to query the home agent to obtain the mobile node’s COA (steps 1 and 2 in Figure 7.26).

When the mobile node moves from one foreign network to another, how will data now be forwarded to the new foreign network? In the case of indirect routing, this problem was easily solved by

updating the COA maintained by the home agent. However, with direct routing, the home agent is queried for the COA by the correspondent agent only once, at the beginning of the session. Thus, updating the COA at the home agent, while necessary, will not be enough to solve the problem of routing data to the mobile node’s new foreign network.

One solution would be to create a new protocol to notify the correspondent of the changing COA. An alternate solution, and one that we’ll see adopted in practice in GSM networks, works as follows. Suppose data is currently being forwarded to the mobile node in the foreign network where the mobile node was located when the session first started (step 1 in Figure 7.27). We’ll identify the foreign agent in that foreign network where the mobile node was first found as the anchor foreign agent. When the mobile node moves to a new foreign network (step 2 in Figure 7.27), the mobile node registers with the new foreign agent (step 3), and the new foreign agent provides the anchor foreign agent with the mobile node’s new COA (step 4). When the anchor foreign agent receives an encapsulated datagram for a departed mobile node, it can then re-encapsulate the datagram and forward it to the mobile node (step 5) using the new COA. If the mobile node later moves yet again to a new foreign network, the foreign agent in that new visited network would then contact the anchor foreign agent in order to set up forwarding to this new foreign network.

Figure 7.26 Direct routing to a mobile user

Figure 7.27 Mobile transfer between networks with direct routing